Installation Views

Video

Works

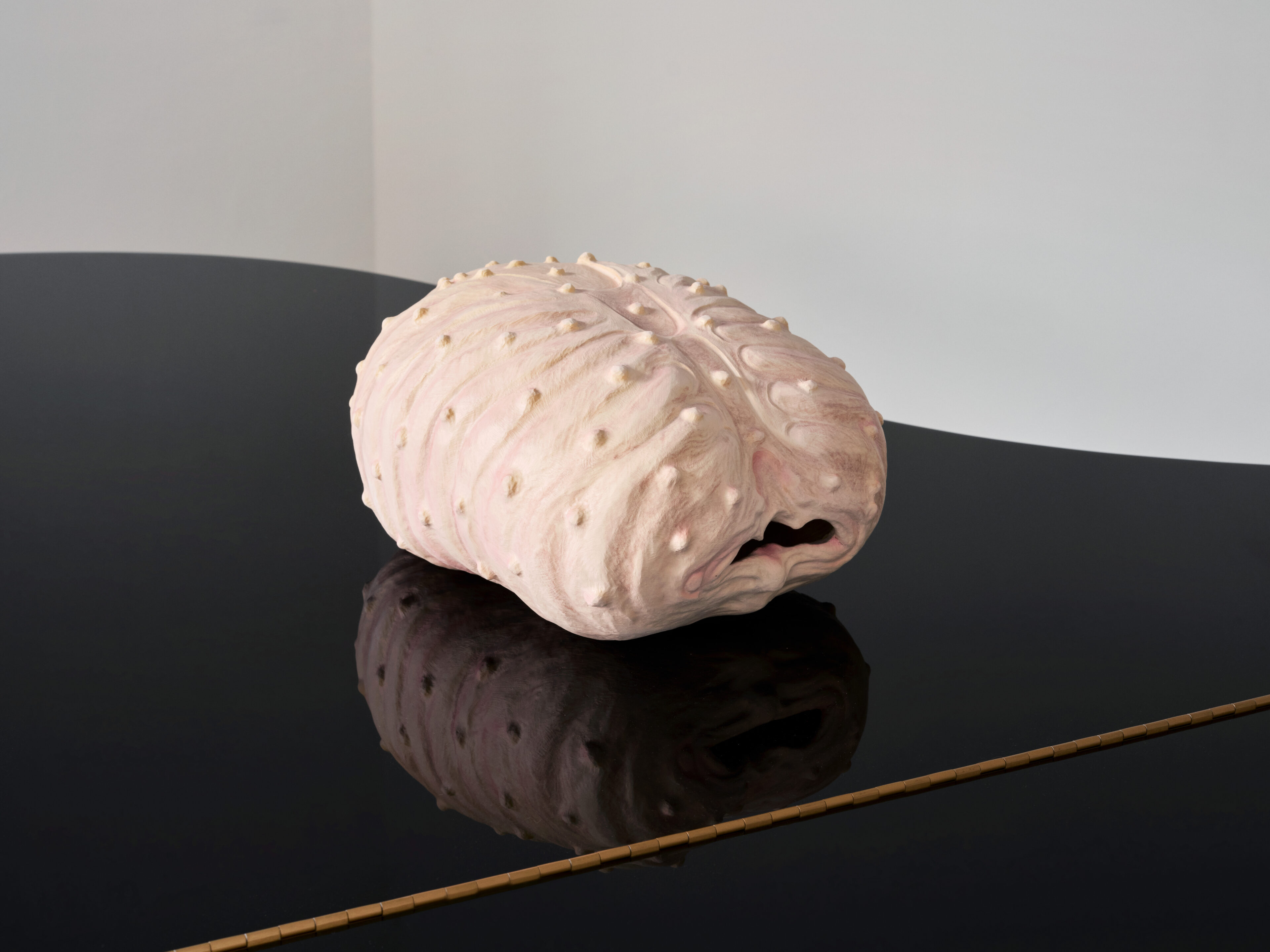

The feelings of an empty home, filled with cake and roast dinners, snacks, tea and biscuits, root veg, white sauce, cheddar cheese, 2024, Ceramic, acrylic ink, 21 x 25 x 12 cm

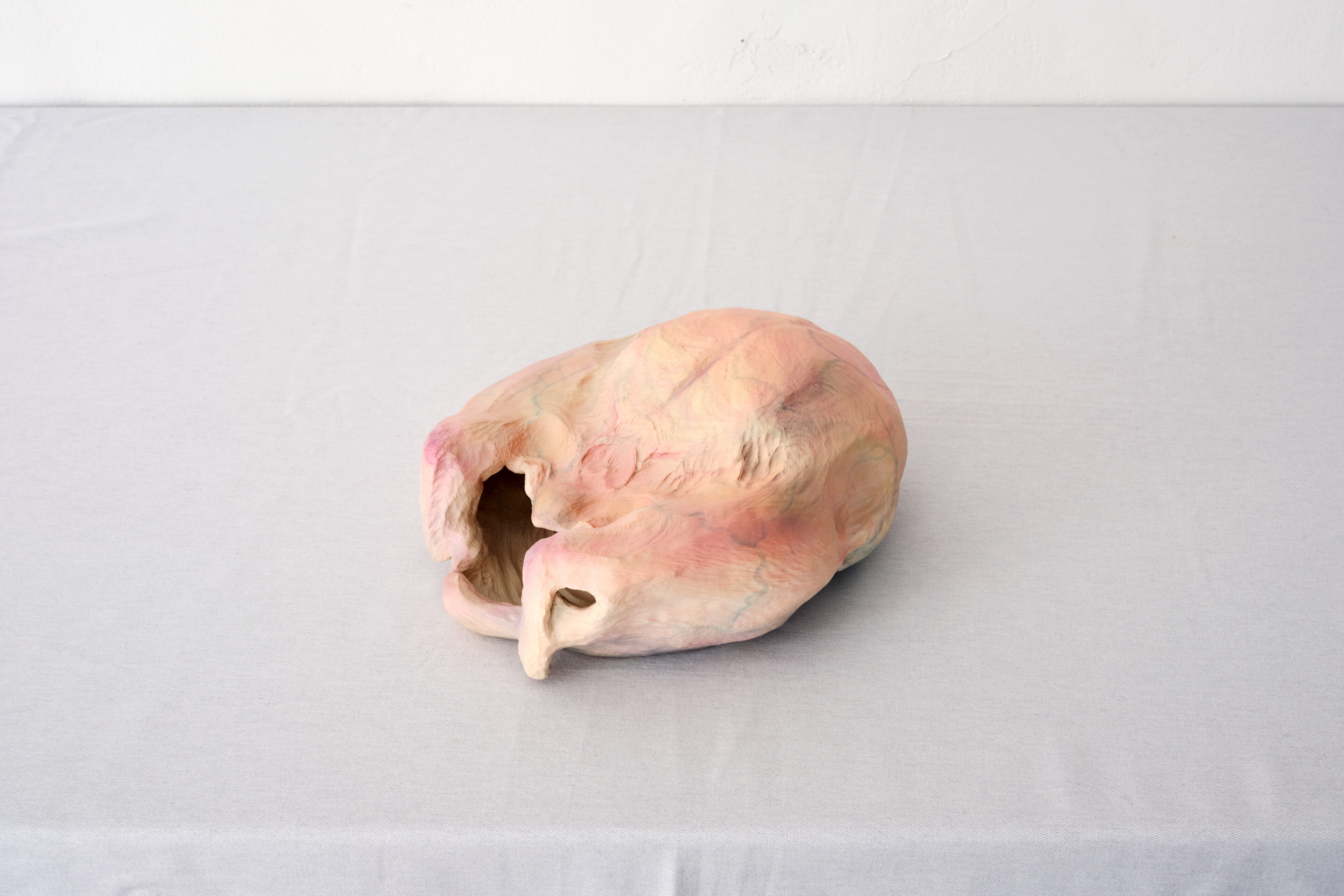

And the Uterus, itself a demon, a trickster, who moves about at night, or even while you’re awake, but you can’t see it, and it might be up in your head, or up high in your throat, or maybe it even gets out of you altogether and chokes the cat, or tips over and breaks the bowl your parents got as a wedding present., 2024, Ceramic, acrylic ink, 19 x 22 x 12 cm

Press Release

You walk into what looks like a post war apartment block, there’s a

modern metalwork panel that serves as a gate or a screen, very modest,

not far from the tram stop. Past that and into the cloister around a

garden quadrangle, its a bit Monastery or Nunnery, but with a modern

concrete block with balconies looking over.

You go up the stairs to the side door at the back of the church, at the top

of the steps is the door, the doorknob is made of brass and you can’t

operate the handle without pushing your finger into Satan’s arsehole as

you push down on the handle, because he’s astride the handle like its a

broomstick and he’s got his bum in the air waiting for you, so you have

to do it otherwise you can’t get in. That’s the deal. After that you get

inside. You’re going to hurry past the lions, the velvet bell ropes and the

old lady behind the postcard table, just mutter a Hallo, and you’ll ignore

the historical context panels showing the bomb damage and the images

shot from above, the aerial photos of the aerial bombardment leaving a

gaping hole, opened up down to the crypt spot on exactly where you’re

headed. Right through the floor. On the left is the blue-grey faced

woman, lying beautiful, stone faced, then, right. Once you arrive to the

central cross of the nave where the church turns around itself like a train

on a turntable, surrounded by resplendent Arabic arches like the ones

from Cordoba down in that cistern – with alternating red and white

stone stripes, jolly, and onion domes – you turn with the train and

approach the side chapel, disembark at this one with white washed

drapes, and white washed walls, and a fresh cut red carnation centerpiece,

atop a little wooden alter which mainly serves to get in between you and

him, to keep you from getting too close to his feet, pinned through with

that one nail driven through the both, his varicose veins pulsing as the

blood trickles out slowly by now, congealing.

The biggest rib cage you’ve ever seen, truly the focal point of the whole of his being,

the focal point of the whole of this church, off to the side, but in the center

nonetheless. A wedge shaped chevron of a sternum cantilevers out above his soft

boneless expanse of belly, with all his soft organs behind taught skin, puckered with

pustules, stuffed with garlic under the surface of the skin, knife pricks, puss and

blood, willowing-out like tears, but the lungs aren’t behind the ribcage, the ribcage’s

keeping them prisoner. And, his chest heavy, heaving heavily and tearing up his skin

tearing down the zipper between the finger bones deep inside the flat of the hand, by

now pulled up to the second knuckle of his middle finger, and the skin stretching and

bunching up around the nail. Taking his skin off of his hands like a glove as his

weighted breaths, wheezing through his slightly open mouth, whistling past his little

milk teeth, tug him down further against the inertia of the mass, straining under the

weight of his heavy torso filled to the brim with trinkets, knickknacks and whatsits,

and whatsits, each wrapped lovingly in a square of sky blue silk, with notes like inside

notes like inside a fortune cookie, twisted into their gossamer wrappings. Bits of old

Bits of old nail and bone, splinters of cross, wads of sage, all got in through the

wound on his side, or even rammed through his mouth and down his throat, past his

vocal chords, down his larynx to his lungs. They clamor for space besides the breath.

The filled cavity of our chests. Empty with air.

And Christ over here, an empty cavity, a cavity stuffed with stuff.

So, write freely, without the disintegration of my body, while I lay there dropping out, slumping, slack. Going up.

Losing myself to the pillow. Lolling head. I feel sick again mum, I’m rotten in the stomach again.

I thought they were all empty, but they are filled with breath.