–

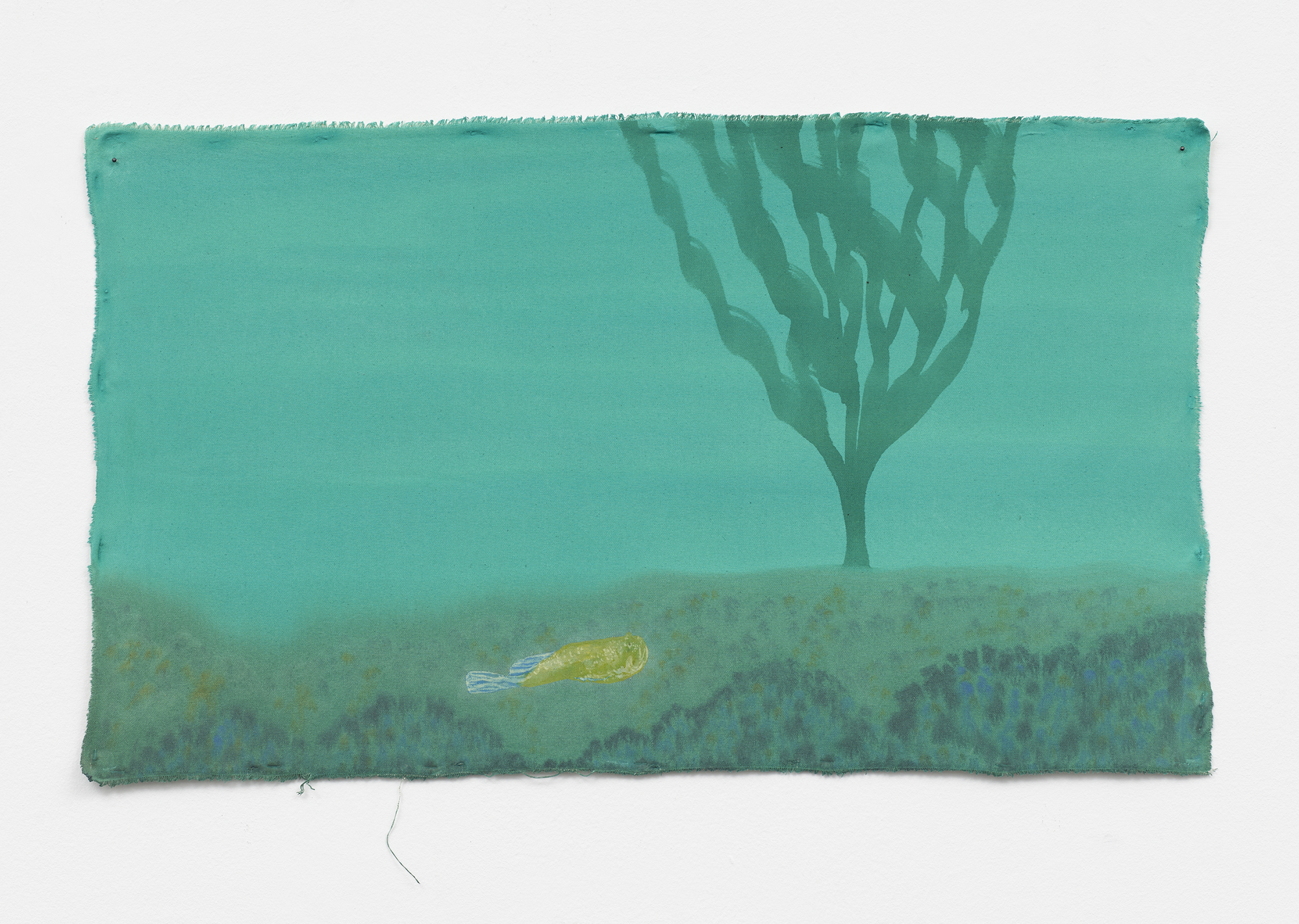

Landschaft

Lutz Driessen

Fatma Güdü

Merlin James

Behrang Karimi

Cosima zu Knyphausen

Stanislava Kovalcikova

Lotte Maiwald

Kaoli Mashio

David Ostrowski

Sale Sharifi

Trevor Shimizu

Installation Views

Works

Press Release

If painting does not seem like a battleground anymore in light of its tolerated normality, its capacity to store subjectivity still allows for exchanges at daggers drawn. What is certain is that the medium plays out as the most socio-culturally constructed one, becoming the perfect vessel to reflect on the various systemic structures it is subjected to. A landscape exhibition could then very well start with the premise of an inward gaze, as if painters would be the ones better suited to apply strategies of introspection. But the pure sight is compromised. Painters are also socio-cultural products that developed over time: after the attentive looker that depicted the world “with a sincere hand and a faithful eye”1 came the subject located in mass visual culture and a new standardization of vision. With always the same request: that painters make us see.

But to visualize what? In a contemporary world supposedly poor in singularity2, how can an individual subject claim to own her own perceptual experience? In the swamp of our collected perceptions, Landschaft shows the painters’ decided commitment to depiction as an honest enterprise in the sense of an applied enjoyment, like a child sticking her tongue out when drawing. If landscape painting is supposed to show a place, here what unfolds is closer to a psychogeography of our feelings, a satisfying pastoral juice.

Landscapes can exist in this gap, stretching the cognitive wish for uniformity to prefer a reading that owes more to the peculiar wryly way painters do their craft, surfing the wave of deference. The various landscapes in the exhibition expand to contain more and more things and to stretch the poles, between what constitutes them, between periphery and center, heart and home, impression and shape, taste and cliché, artistic practice and tourism, peinture en plein air and the comforting isolation of the studio. All the details become visible, and the landscape feels natural not because it is a truthful depiction made with care, but because it sits in the repeated exercises of attention. It brings all the elements in a simultaneity, an expended dimensionality of the field. Something truly panoramic but with an aftertaste that smells heavy, Giverny turned into a perfume.

Paolo Baggi

–

1 Coming from Svetlana Alpers’ The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century of 1983 and originally from Robert Hooke’s Micrographia of 1665. 2 Jonathan Crary, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, London, New York: Verso Books, 2013