–

“Little ‘Sandy Beach’ Boy”

Installation Views

Video

Works

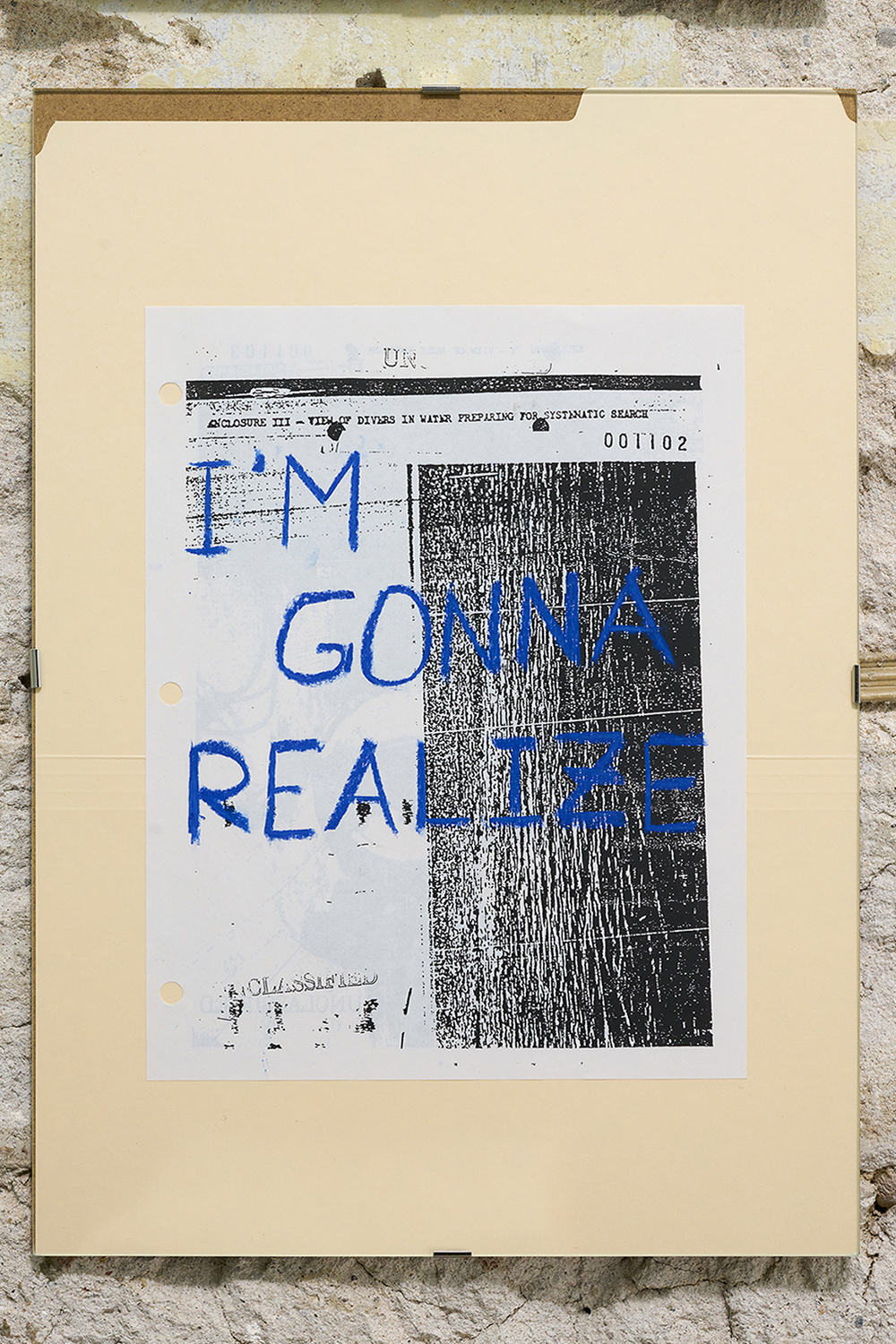

ENCLOSURE II (I‘m gonna realize), 2022, 27.94 x 21.59 cm, blue charcoal on Final Removal Site Evaluation Report Volium I of III, Appendix B, Marine Salvage Records, 001101

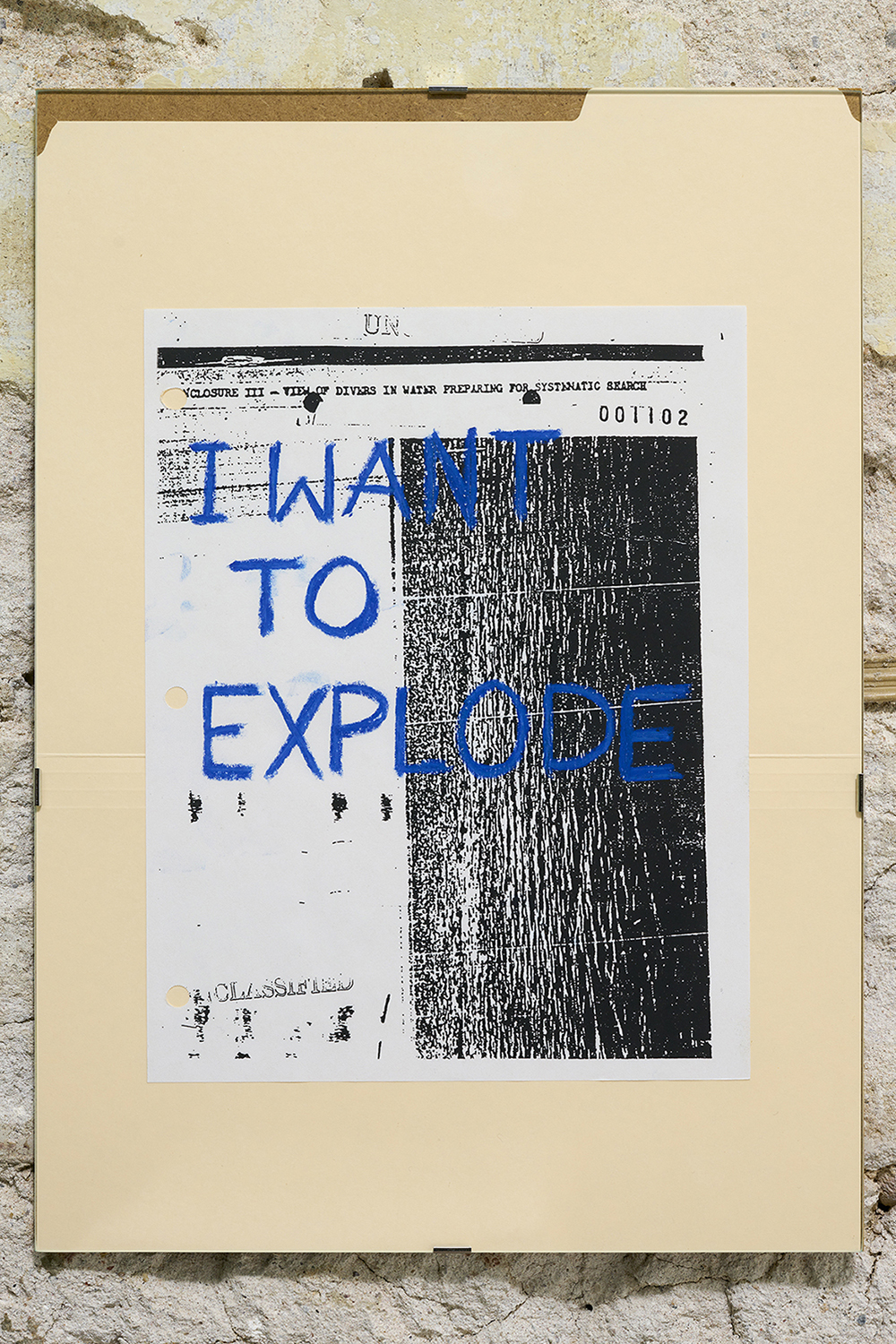

ENCLOSURE III (I want to explode), 2022, 27.94 x 21.59 cm, writing on Final Removal Site Evaluation Report Volium I of III, Appendix B, Marine Salvage Records, 001102

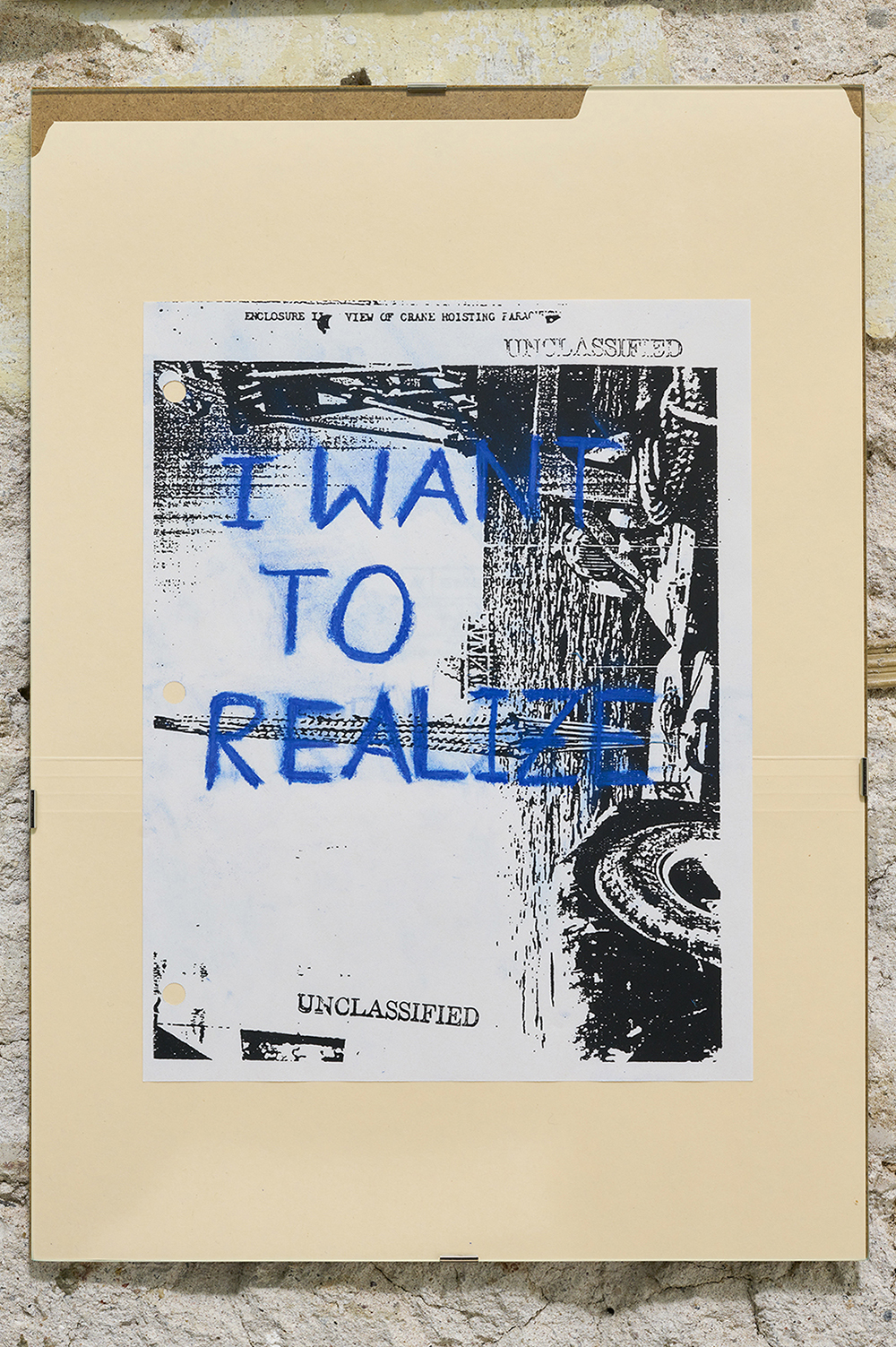

ENCLOSURE II (I want to realize), 2022, 27.94 x 21.59 cm, writing on Draft Removal Site Evaluation Report Volium 2 of 3, Appendix B, Marine Salvage Records, 001101

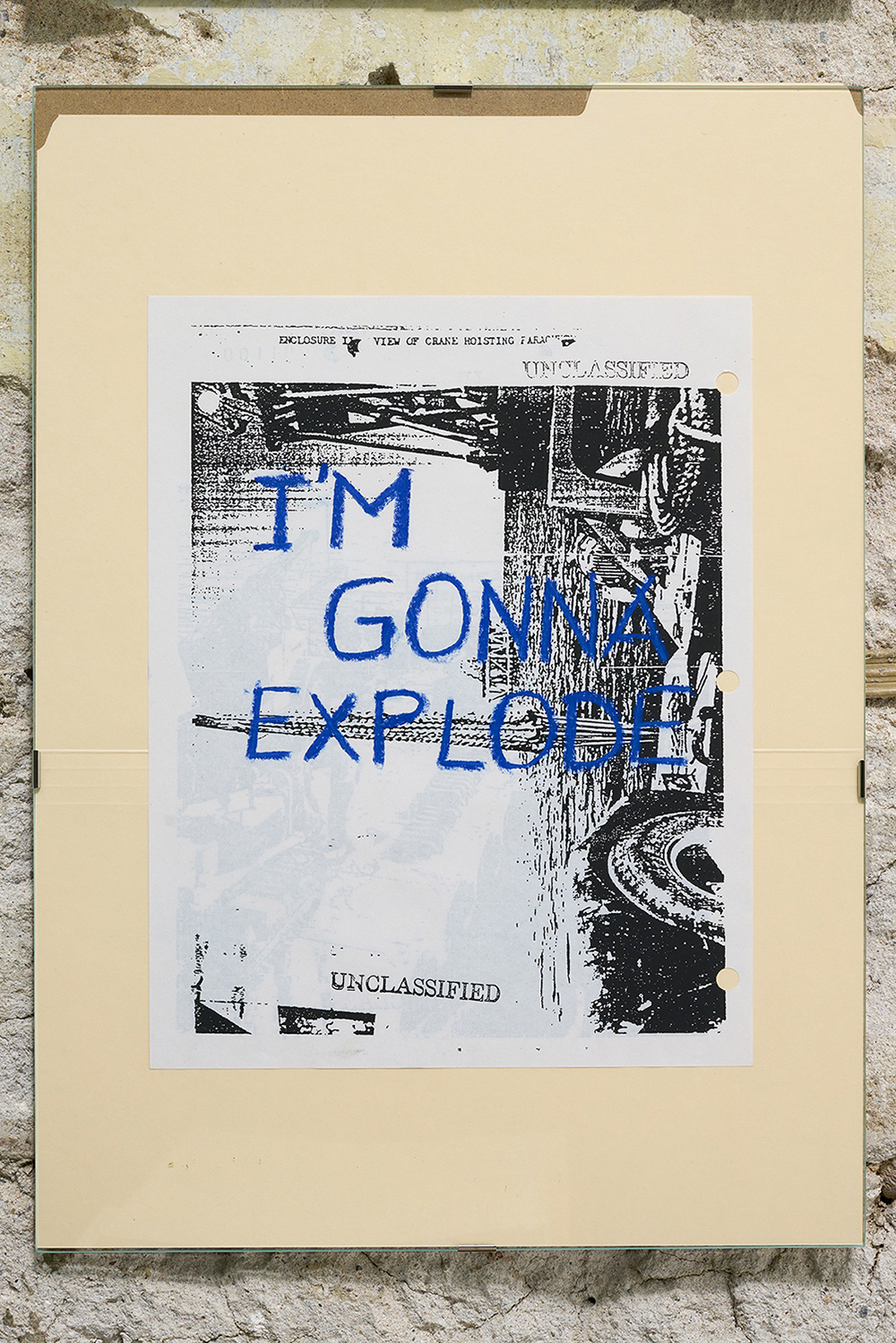

ENCLOSURE III (I’m gonna explode), 2022, 27.94 x 21.59 cm, writing on Draft Removal Site Evaluation Report Volium 2 of 3, Appendix B, Marine Salvage Records, 001102

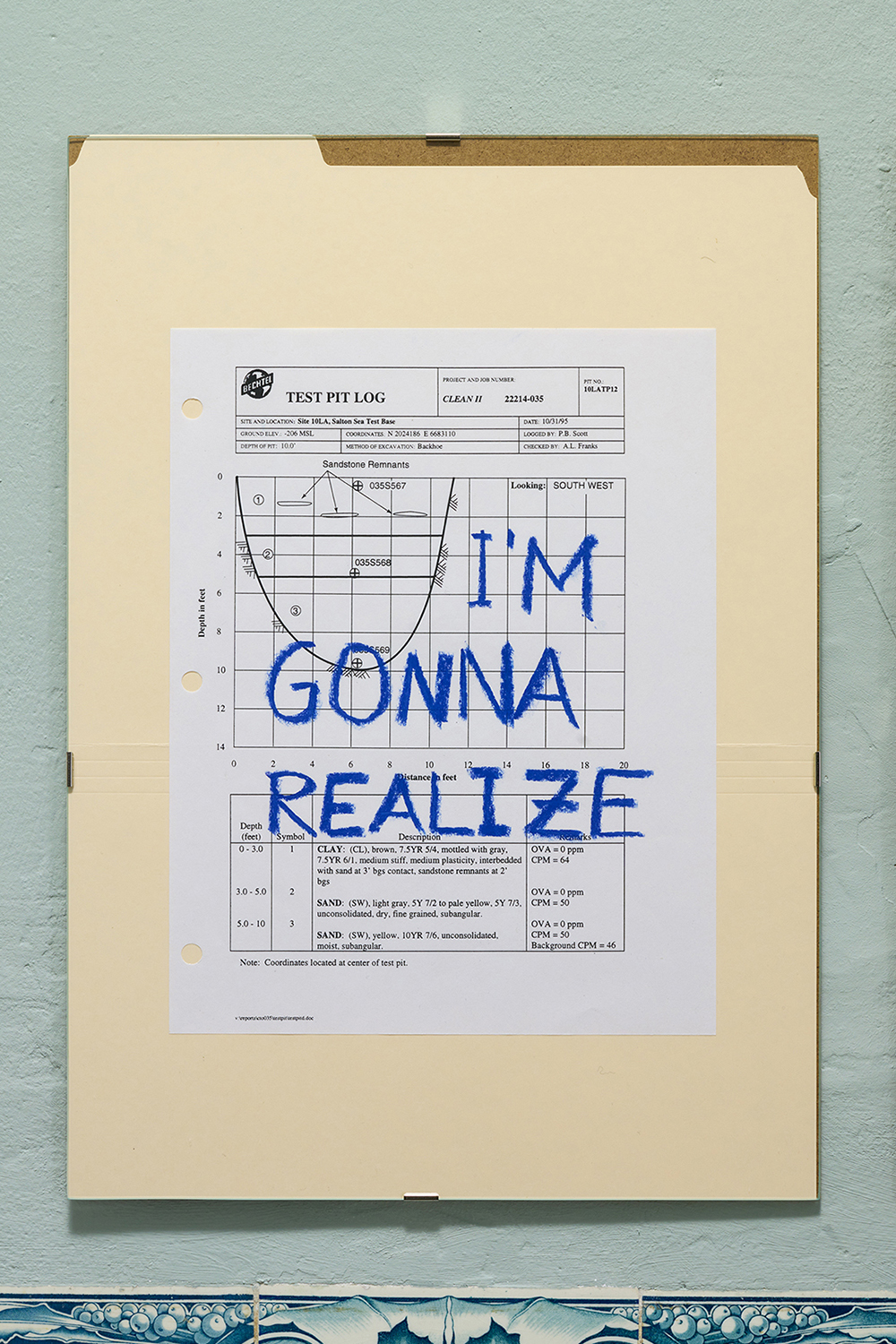

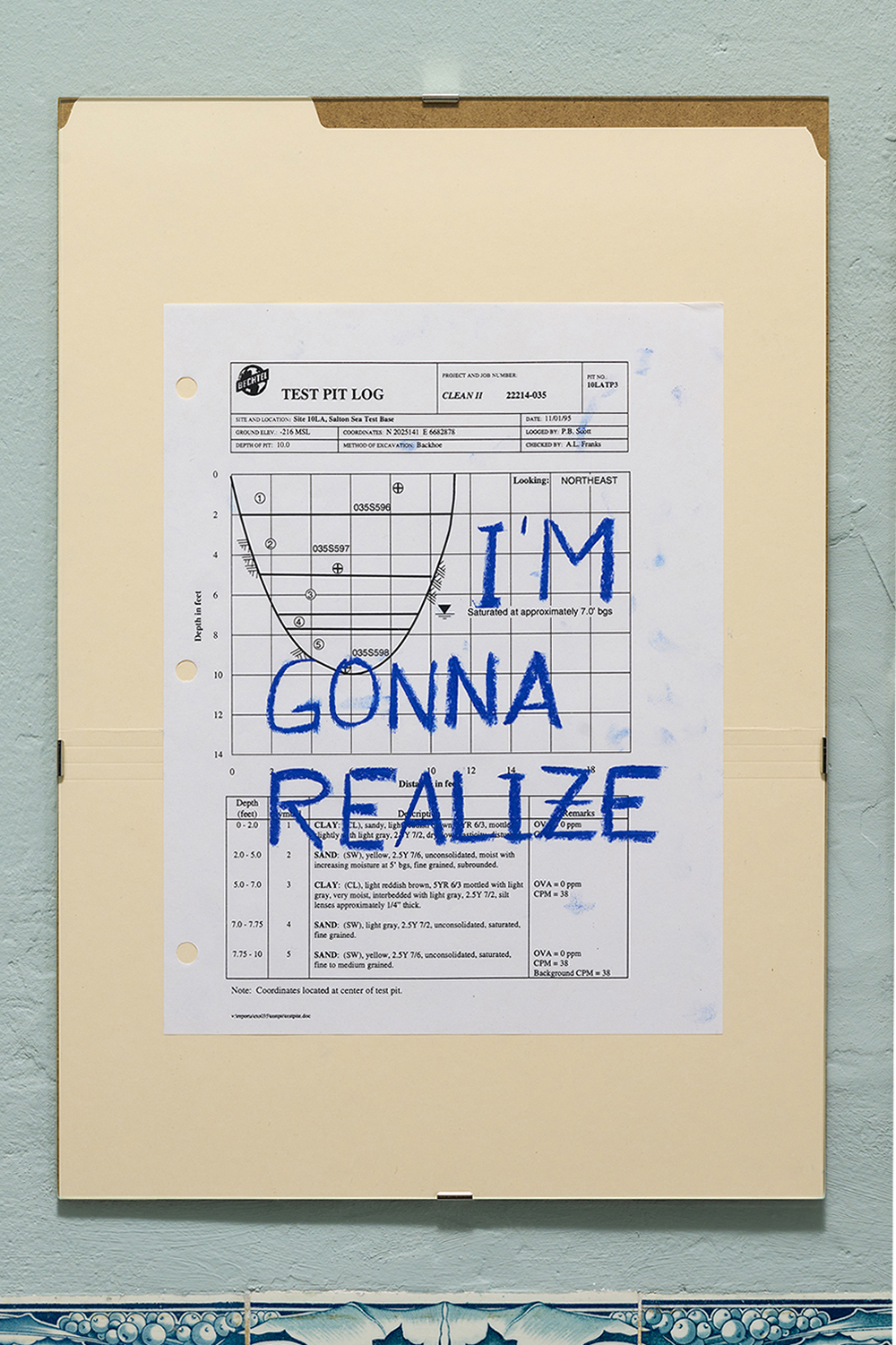

TEST PIT LOG (I’m gonna realize), 2022, 27.94 x 21.59 cm, writing on Draft Removal Site Evaluation Report Volium 2 of 3, Appendix F, Test Pit Logs, 10LATP12

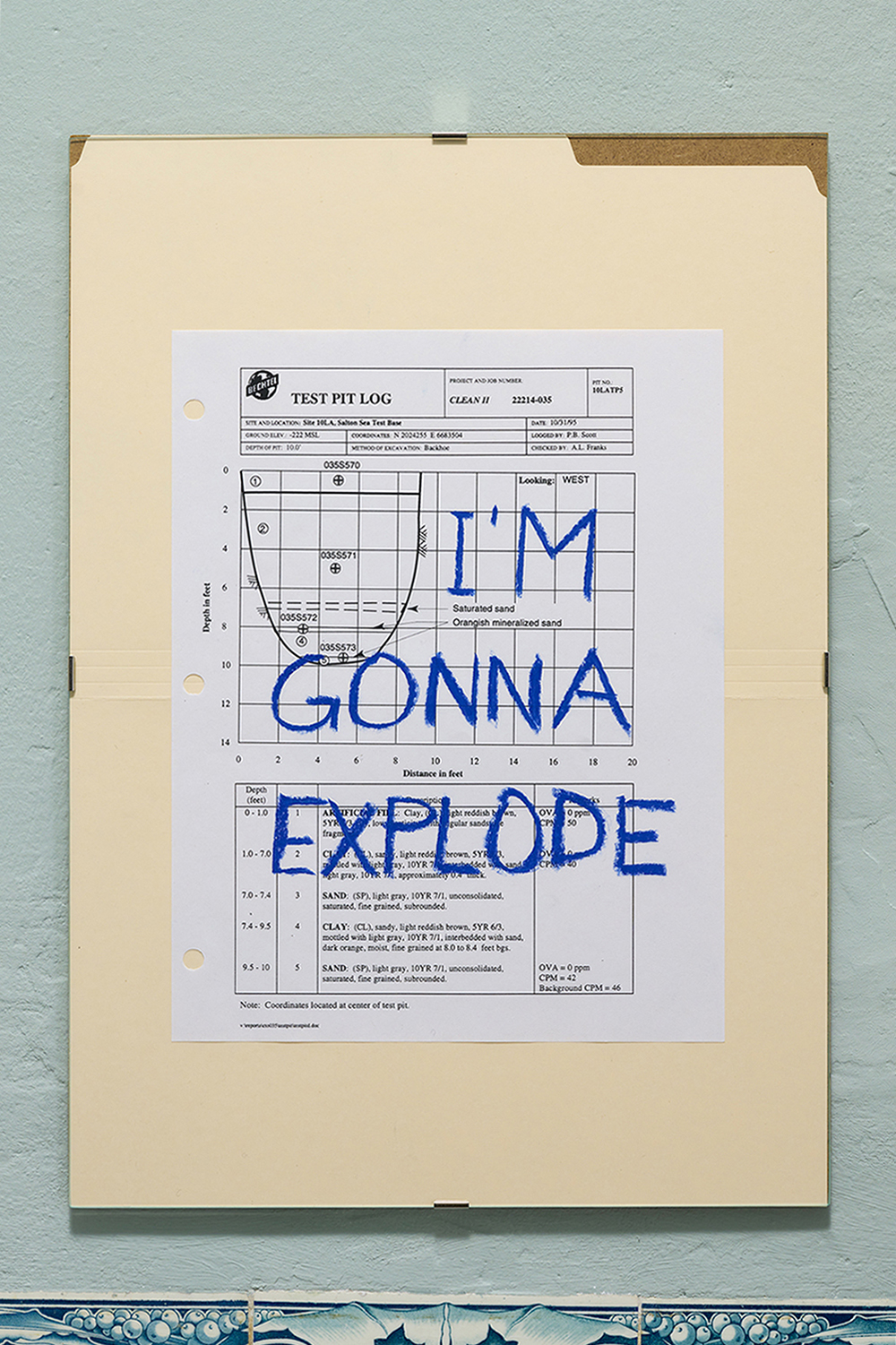

TEST PIT LOG (I‘m gonna explode looking west), 2022, 27.94 x 21.59 cm, writing on Draft Removal Site Evaluation Report Volium 2 of 3, Appendix F, Test Pit Logs, 10LATP5

TEST PIT LOG (I’m gonna realize), 2022, 27.94 x 21.59 cm, writing on Draft Removal Site Evaluation Report Volium 2 of 3, Appendix F, Test Pit Logs, 10LATP12

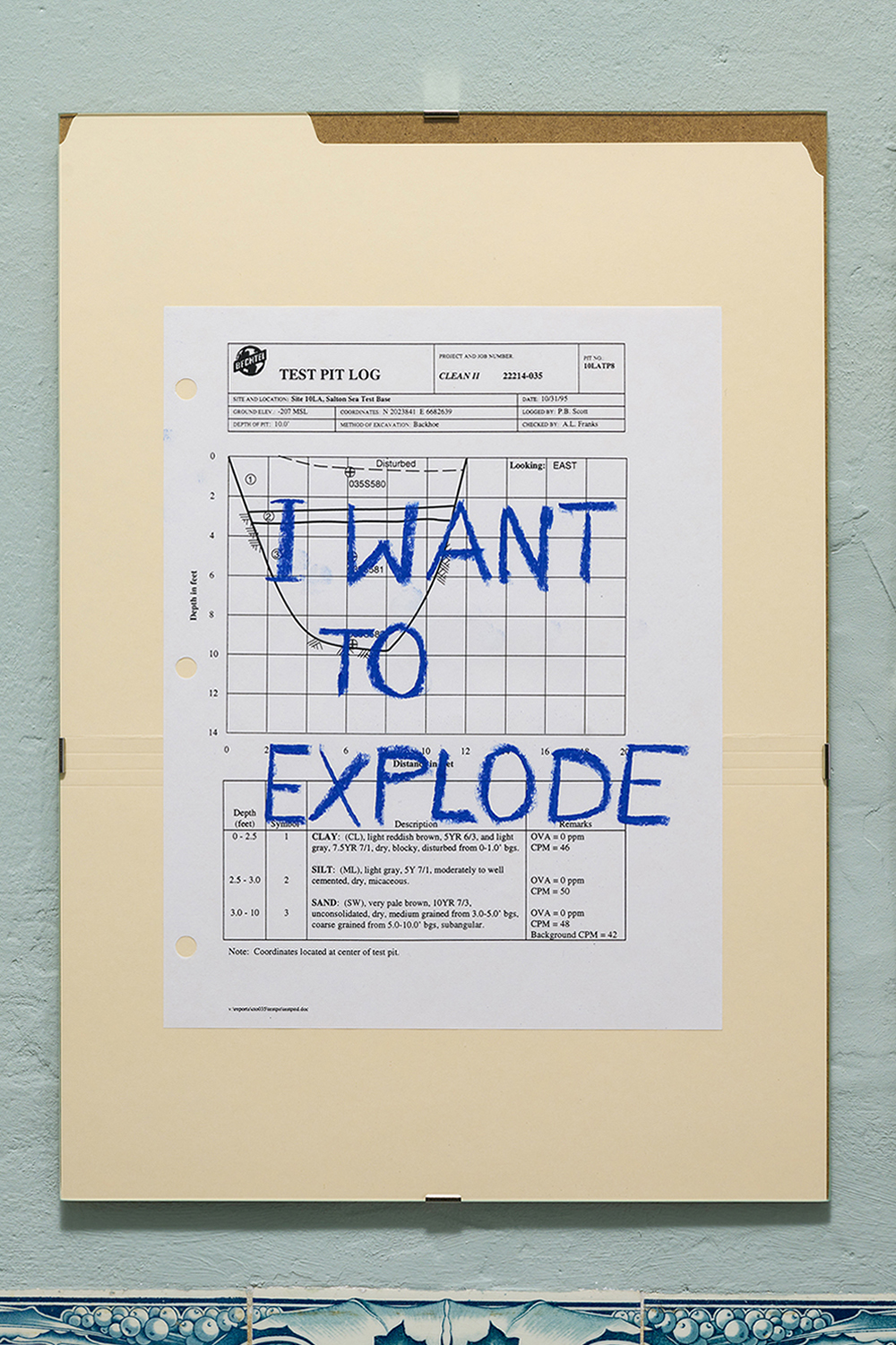

TEST PIT LOG (I want to explode looking east), 2022, 27.94 x 21.59 cm, writing on Draft Removal Site Evaluation Report Volium 2 of 3, Appendix F, Test Pit Logs, 10LATP8

Press Release

There is a great deal of literature in the histories of conceptual art regarding site-specificity. An act, a means, a vessel of making work, which is situated within the unique connotations of a spatial context appears to be the most established way of going about the question of site. Gradually moving away from an understanding of the art object as a clearly defined and independent thing, discussions about the surroundings started pushing the dialogue in a discursive form as opposed to a subject-object oriented constellation. This idea took a very specific meaning following the events in the global history of Land Art, concluding a prominent notion in art writing as early as the 1960s. Traces of this kind of thinking appear to be bleeding through talks and understandings in contemporary approaches. But there has always been a very important and influential divide, between the inside and the outside, between the visibly connotated site where art operates and everything surrounding it or ignoring its persistence.

These structures sometimes present themselves as if brushing over sites that are a little harder to address, to comprehend. One of these happens to be a small shrinking lake located in the southeast most point of California called Salton Sea. Human made, created at the turn of the 20th century by accident when inflow of water from the Colorado River filled a low-lying depression in the desert called the Salton Sink, it evolved to be a very well established tourist point leading up to the 1940s and 50s. Celebrities in the likes of Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby, the Beach Boys and Jerry Lewis used to spend their holidays there, to swim and party, making it all and all a standardized clean version of an all-American escapism dream. The very same site developed into one of the biggest ecological and political catastrophes in the US history up to date.

The works in “Little ‘Sandy Beach’ Boy” consider site in a manner that engulfs factuality and fiction, metaphors, and borrowings. Rooted on a research-based approach they are part of a larger body of work by Lukas Marxt, including moving-image-based works, sculptures, sound pieces and archival material collected over the past five years that documents and disseminates the stories of Salton Sea. Areas of the lake were used in the context of military exercises and preparations by the American army leading up to the creation of the two atomic bombs that were used in 1945. According to now declassified and publicly accessed information the first trials were conducted in this area. Yet these violent histories are invisible on site. Their direct aftermath still plagues local communities and has created a very tangible and real impact on their daily lives.

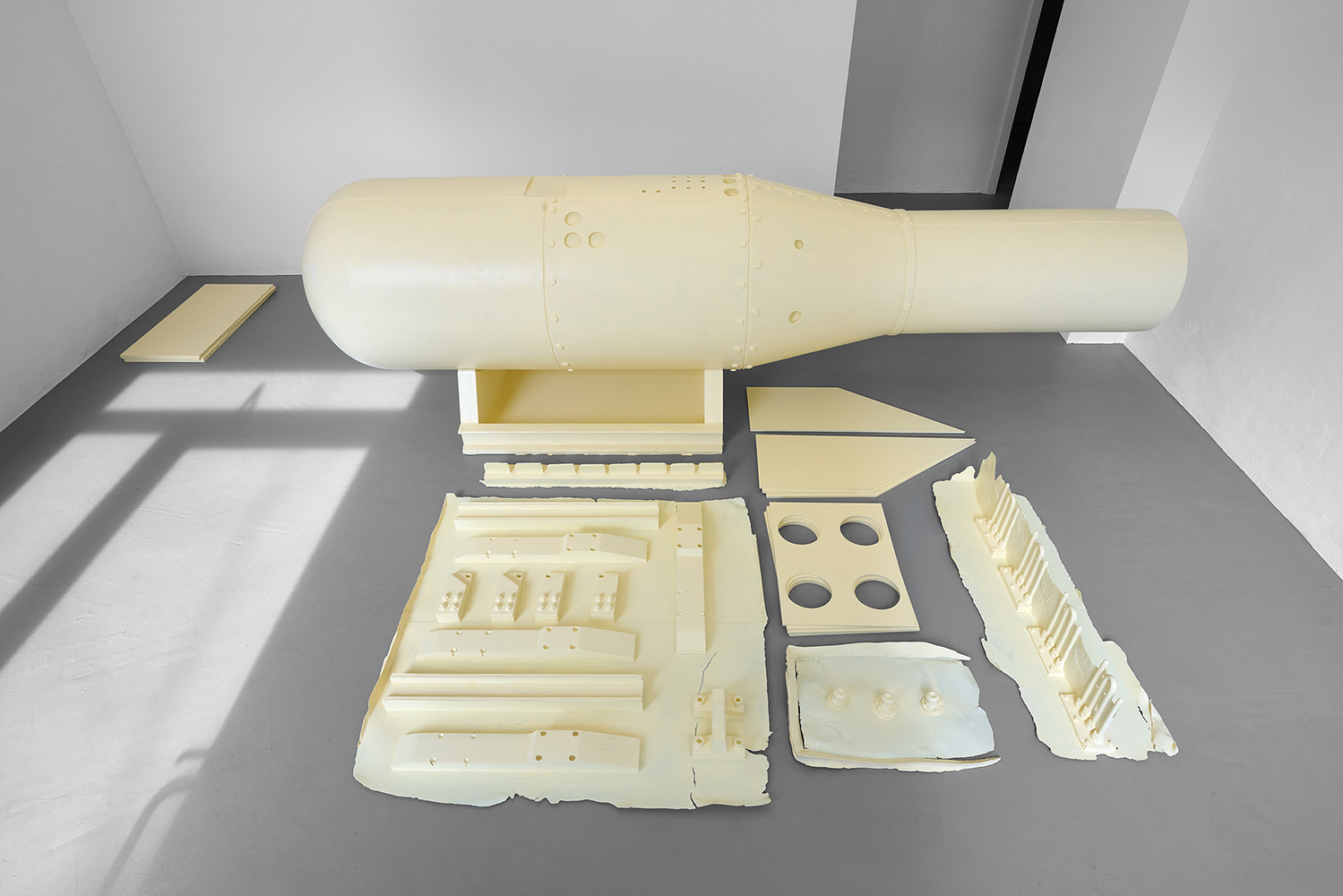

Furthering an artistic interest rooted in archaeological research the works in the exhibition operate through documents and signs. Some of them are re-creations, both in form and design. The one-to-one recreation of the Litte Boy is based off a model, a collectable of military memorabilia that was and still is very popular among certain circles in the US.

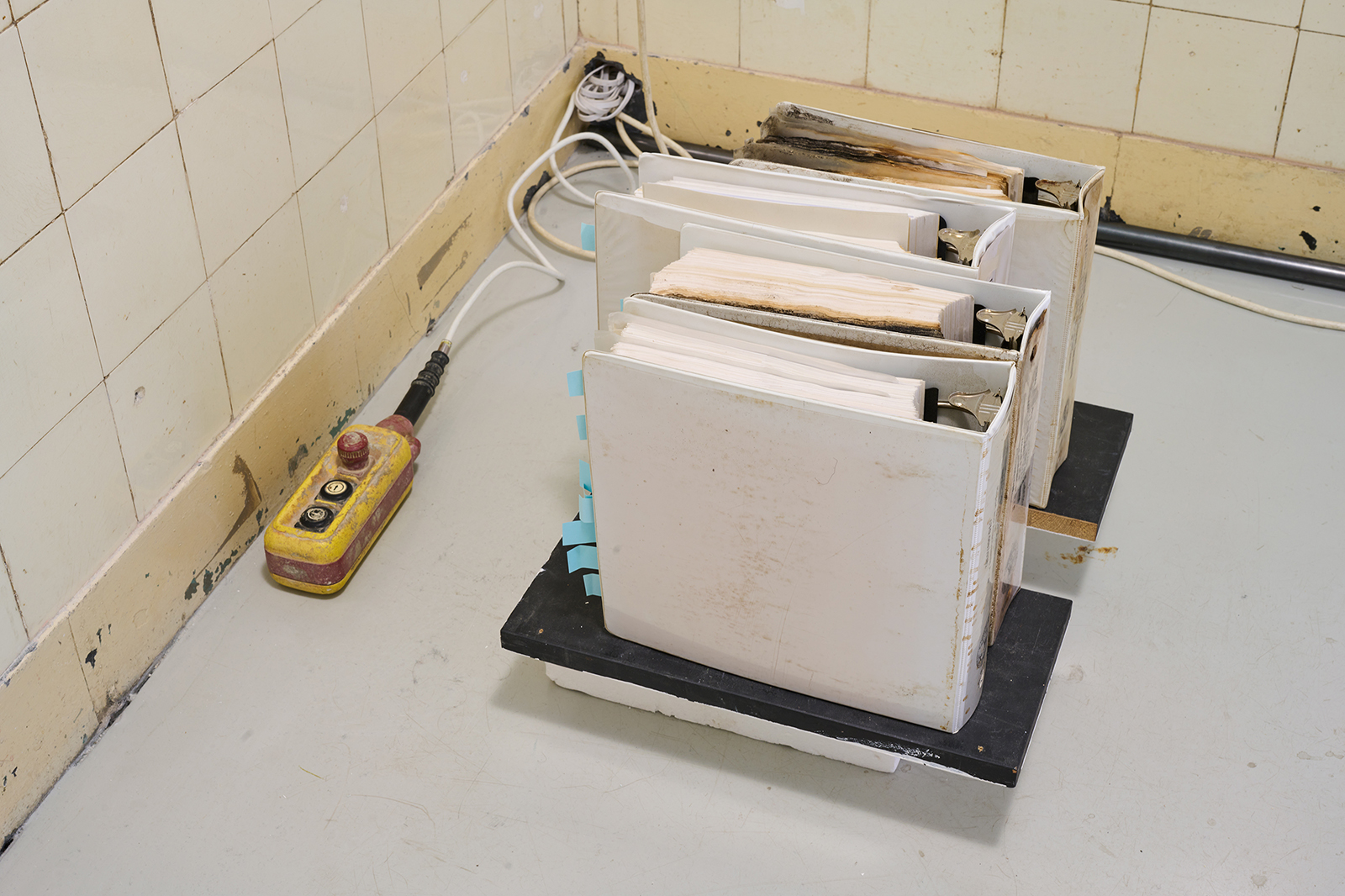

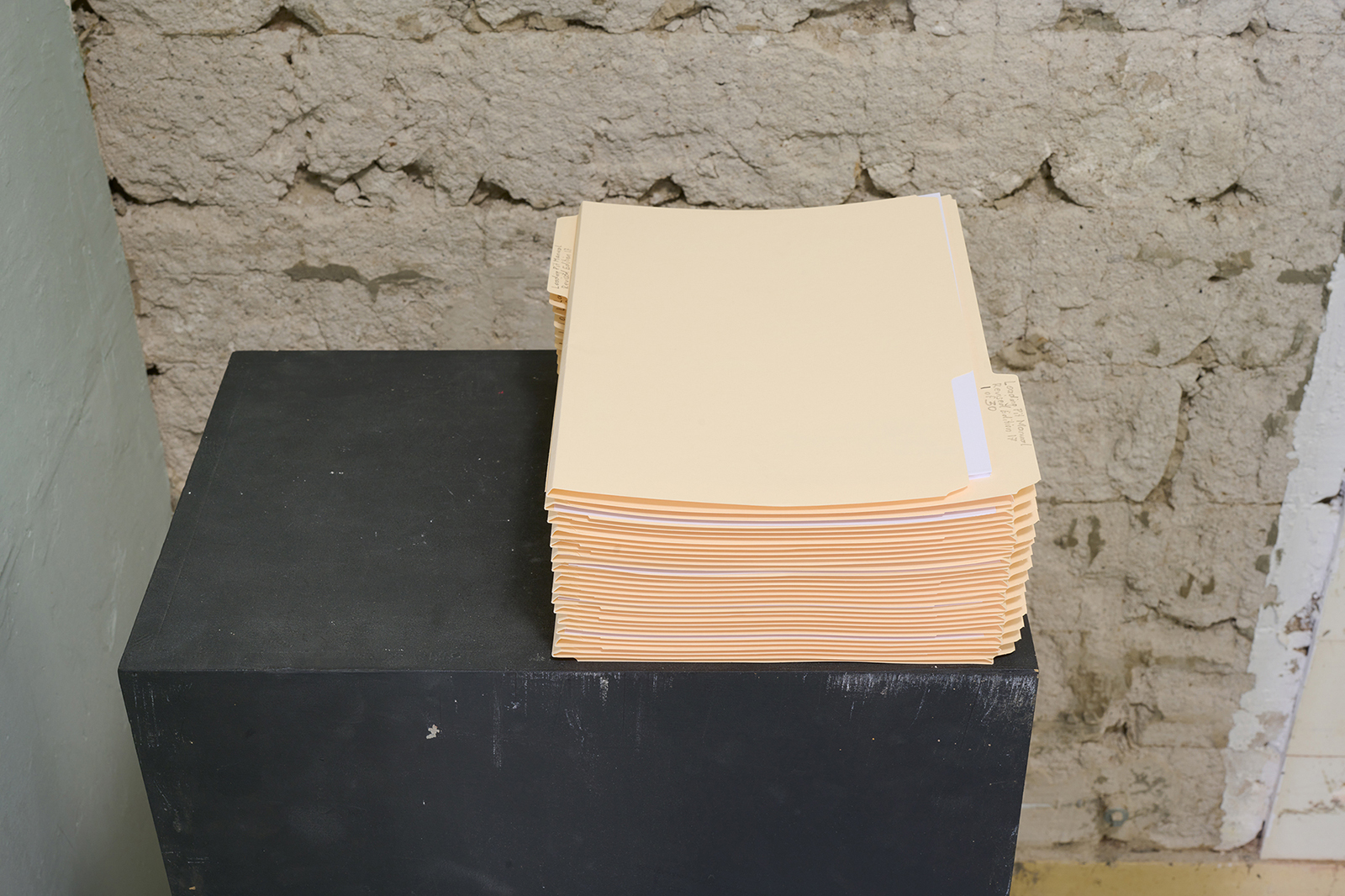

The prototype for the model was not the original bomb but the product of leaked information and speculation that was put together after years of research by a man called John Coster-Mullen, an American industrial photographer, truck driver and nuclear archaeologist who contributed to a public record of the design of the first atomic bombs. He is known for his self-published book Atom Bombs: The Top Secret, Inside Story of Little Boy and Fat Man. The assembly of these objects highlights an important aspect of the story of Salton Sea: the violent heritage of the discourse might be public, but it largely remains unaddressed. The place itself lacks any indicator or insignia pointing towards the past it went through. What bleeds through those stories is the persistence of spectacle and the ways in which it looks at violent storytelling, that very patiently hides itself in the silence. Distributed in the room are archive materials, binders, pages from declassified scraps of information that allude to the processes and bureaucracy conforming the stories at Salton Sea. Two film-works, accompanied by an eerie song stretching out and distorting its original source material the longer one pays attention, deploy a non-human POV to illustrate the pathway of a bomb falling.

The apparatus of the spectacle and operative codes of violence are persistent. They find a way to infiltrate and shape contexts, they break apart sites and institute histories. Traversing through these materials, manuals and scores, reads as a persisting story of a cursed shared experience. But the answer is to be found in the resilience of togetherness. Whilst situating sites facts and fictions present themselves as something of importance; things that we are certain are real and others that will do their very best to proclaim their speculative character. But the divide of speculation and facticity, between the safeguarded man-made and the lived experience of horror and silence is on places like the Salton Sea in a state of constant oscillation.

Sites of this kind keep flickering frantically back and forth.

My eyes will always remain open. This is, to me, the loveliest and saddest landscape in the world. It is the same as that on the preceding page, but I have drawn it again to impress it on your memory.

Haris Giannouras