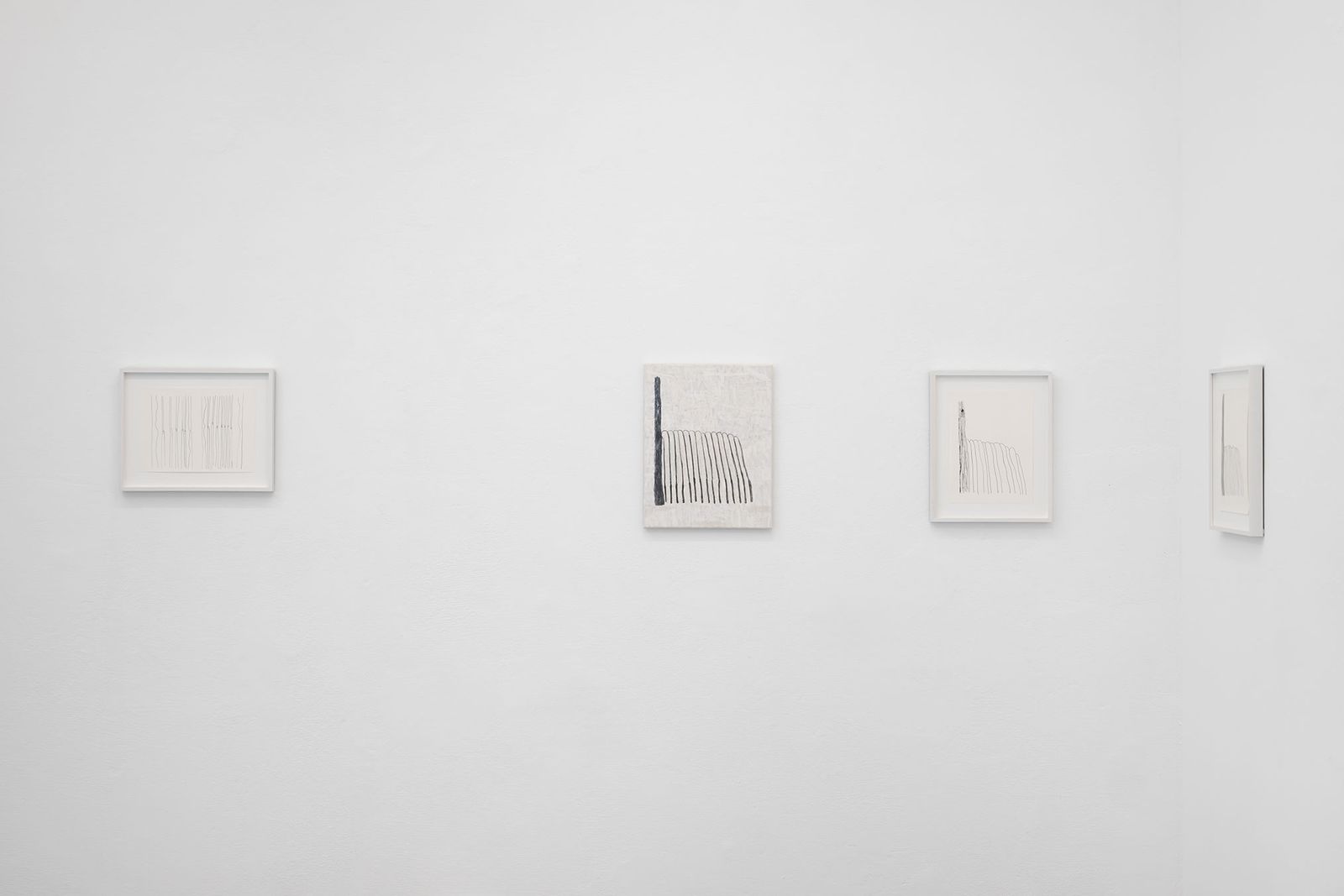

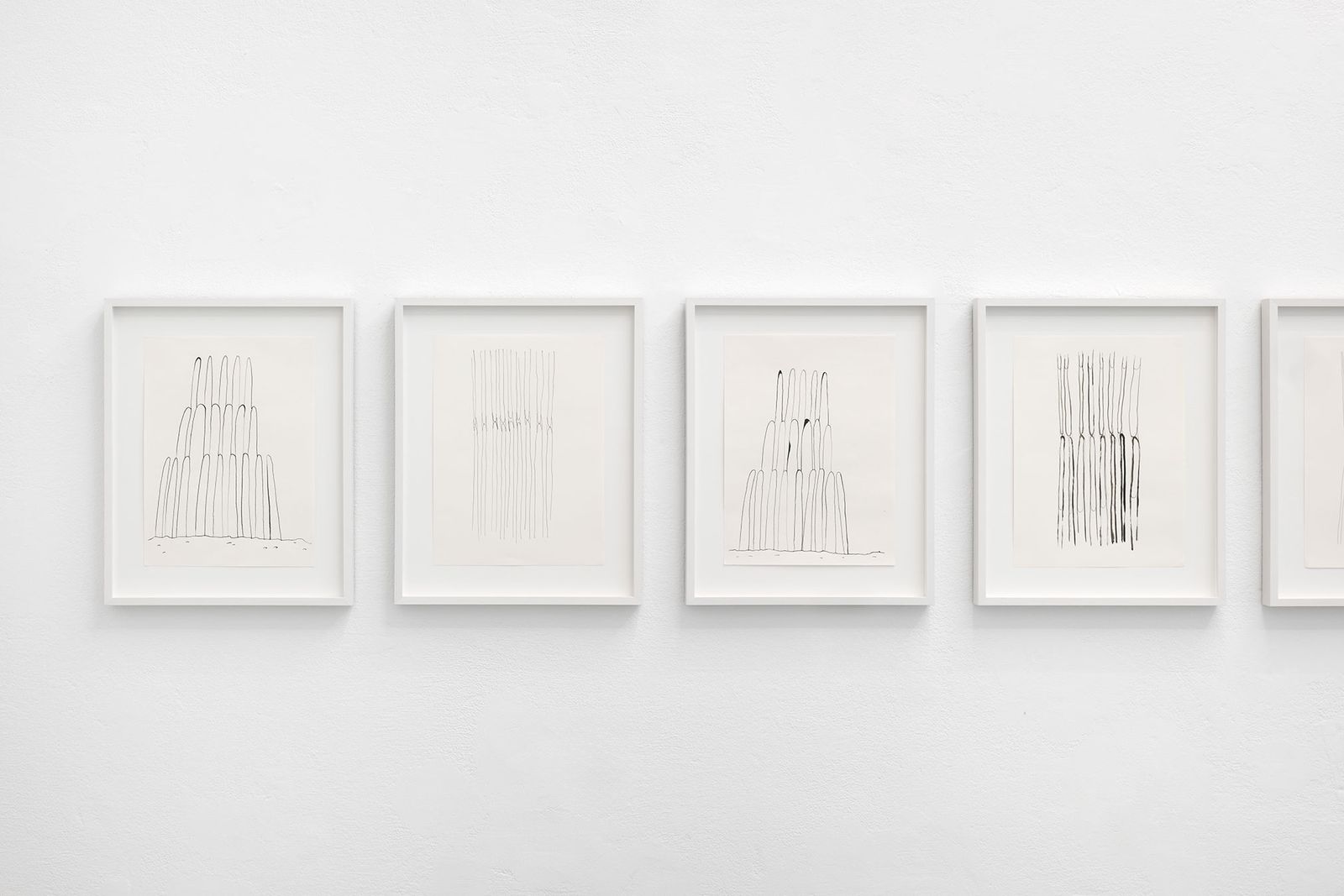

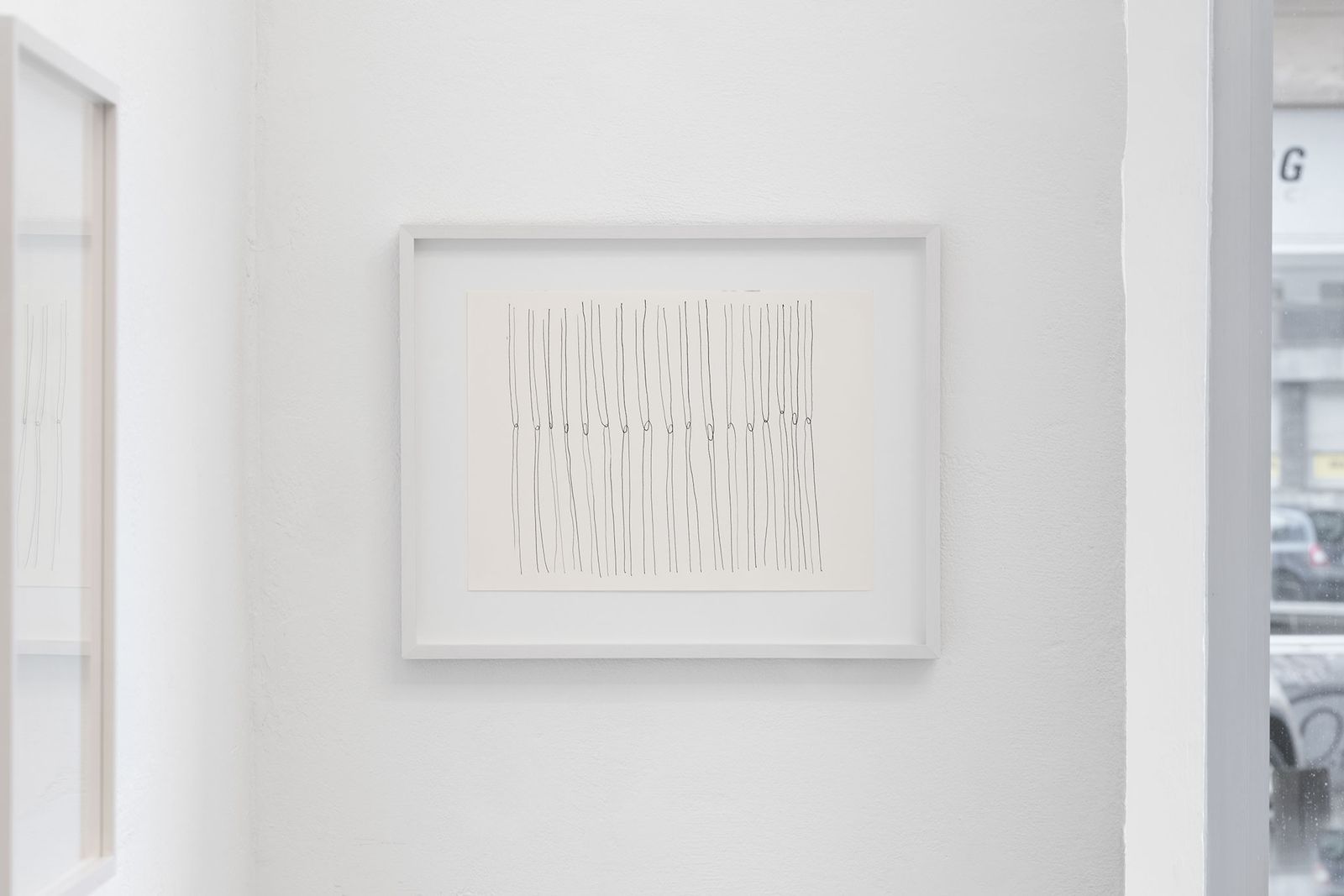

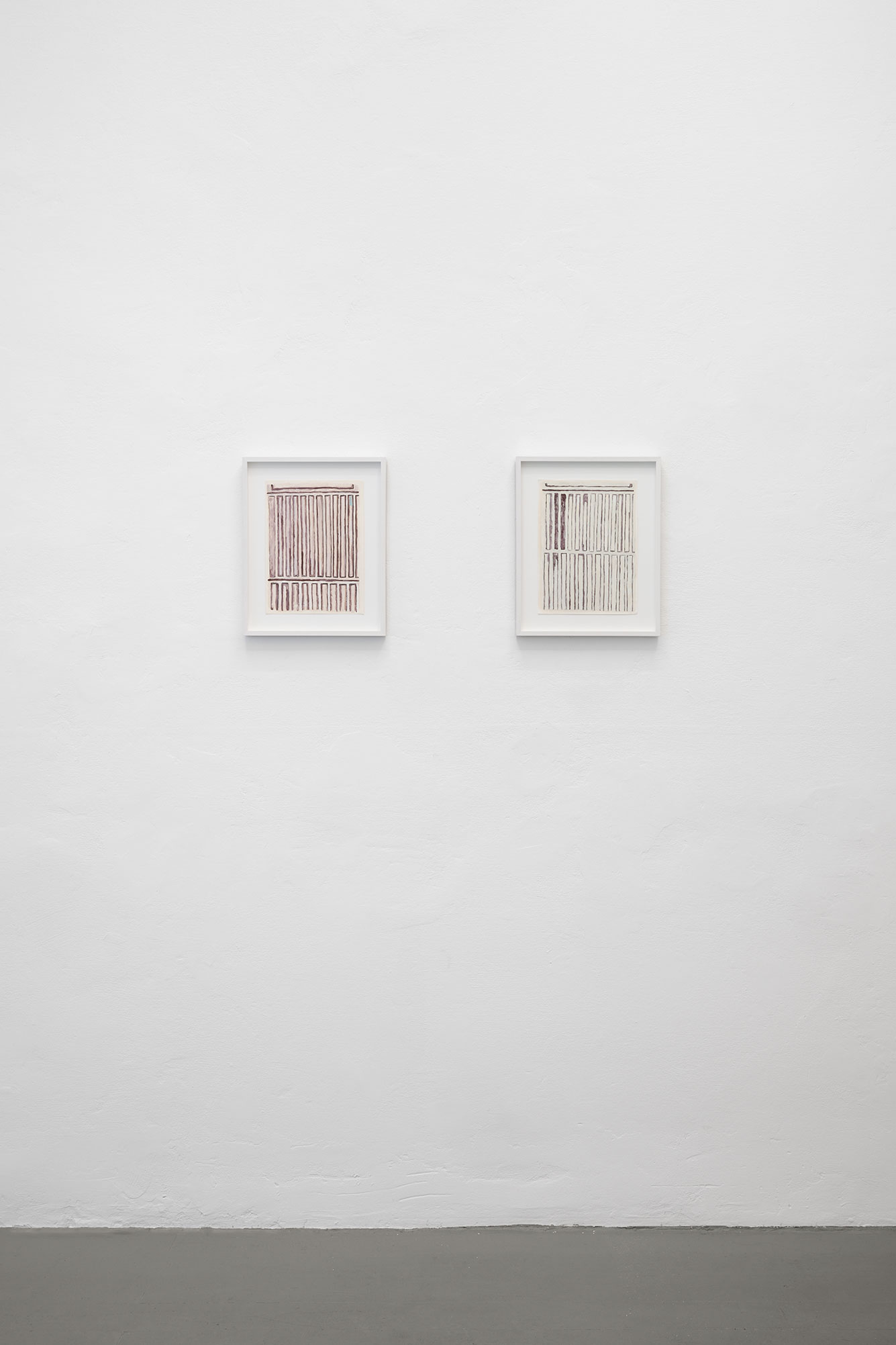

Installation Views

Video

Works

Press Release

Where Art Belongs

For the first time I visited Kaoli Mashio on a balmy summer day in July 2023. Her studio is in the rear courtyard of a building in Düsseldorf. Before she invites me to her tidy studio, the artist shows a plant: shiso, an herb used abundantly in Japanese cuisine, is growing between the bushes opposite the entrance. After a brief digression into ethnobotany, we talk about painting and get straight to her works I’ve come here for: a motif rendered from many different perspectives.

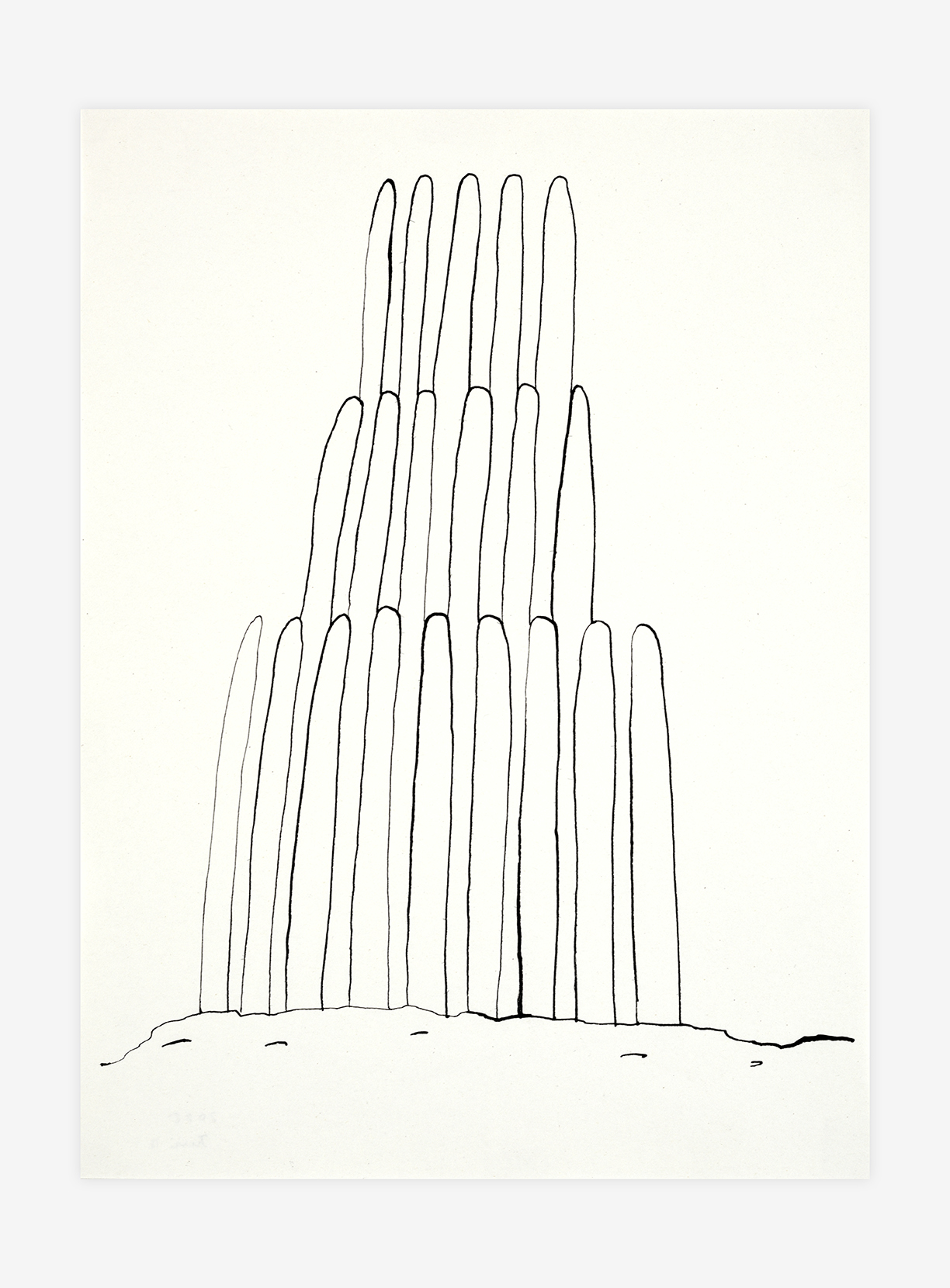

Kaoli Mashio left Japan in 2003, a country whose chasms between modernization and tradition, between public and private, are ubiquitous. An obsession with new technologies is juxtaposed by a more down-to-earth side—a potential consequence of a shrinking population and economic crisis: The further one drives to the countryside here, the more frequently one comes across rusty, weathered building facades made of corrugated iron, a material that spread across the globe after the British patent expired thanks to the entrepreneur Carl Ludwig Wesenfeld from Barmen in Wuppertal. This building material helped to accelerate the generic convergence of the world in the modernist period—but at the same time, it also represents a revenant of the glass and steel from which the magnificent, formal arcades of the nineteenth century were constructed, monuments to the era’s promise of transparency.

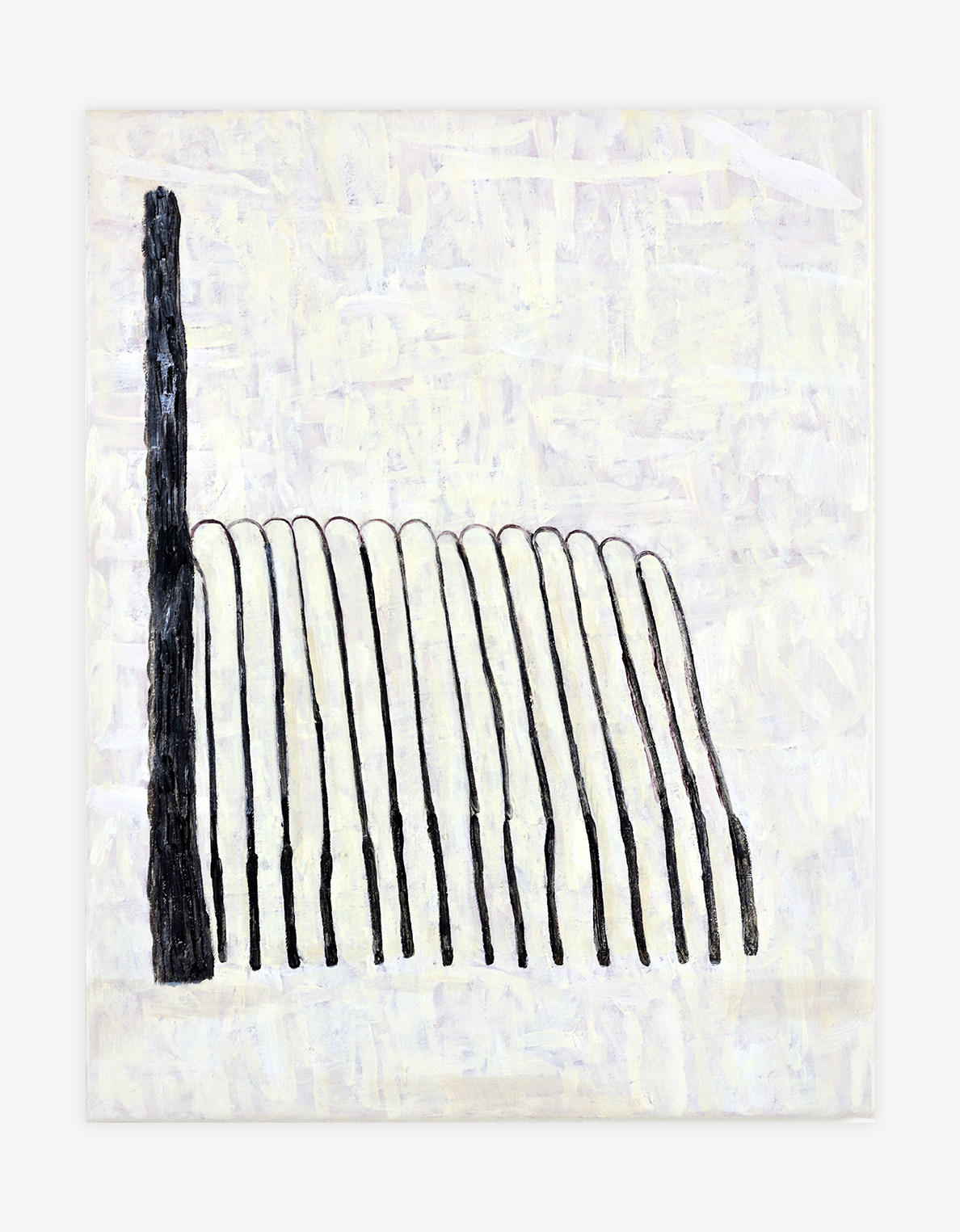

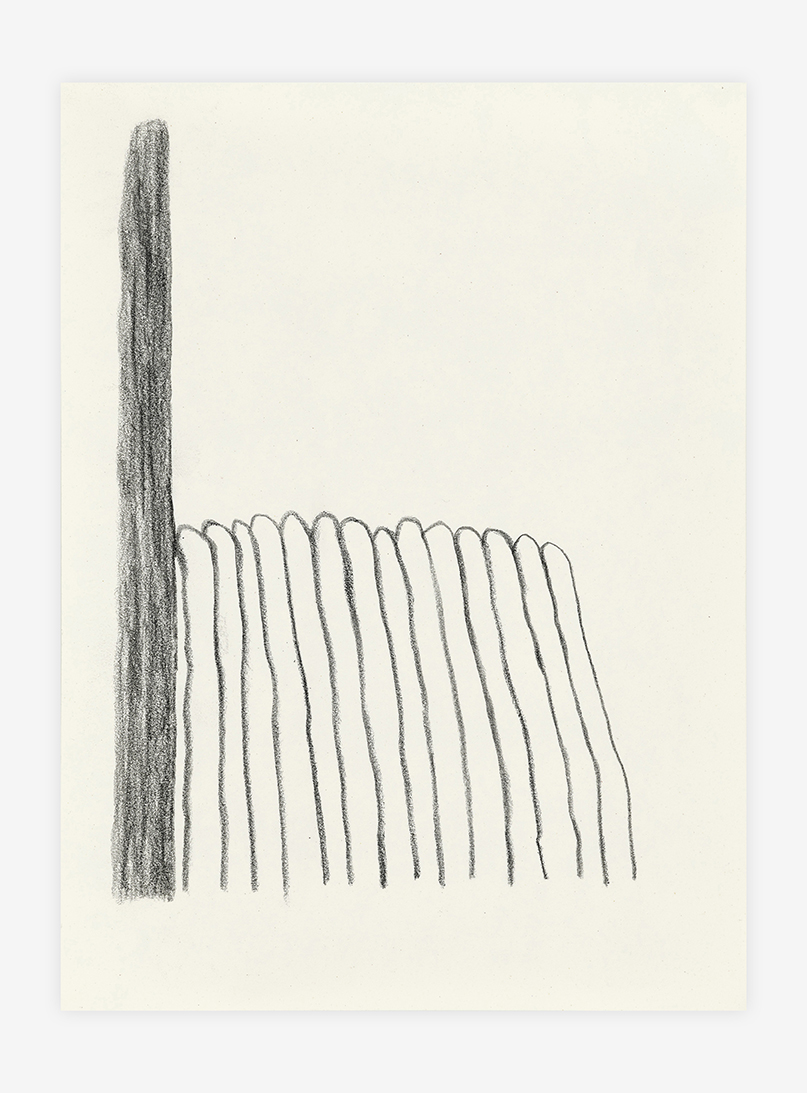

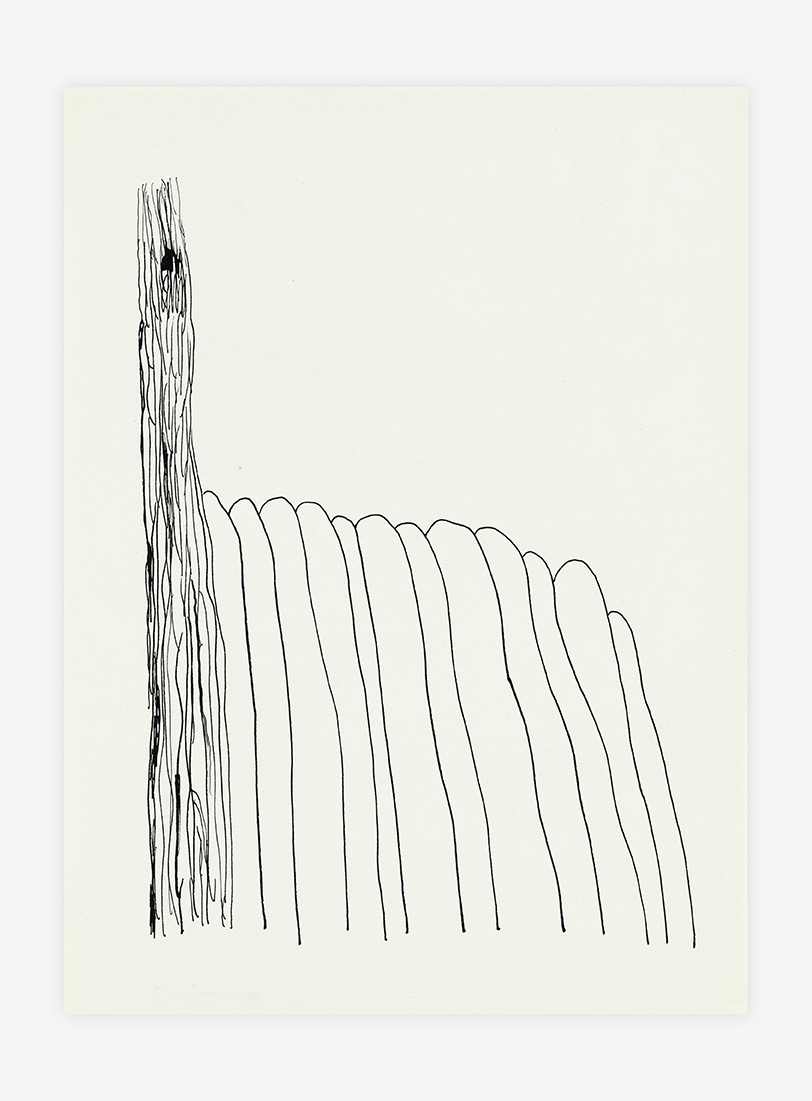

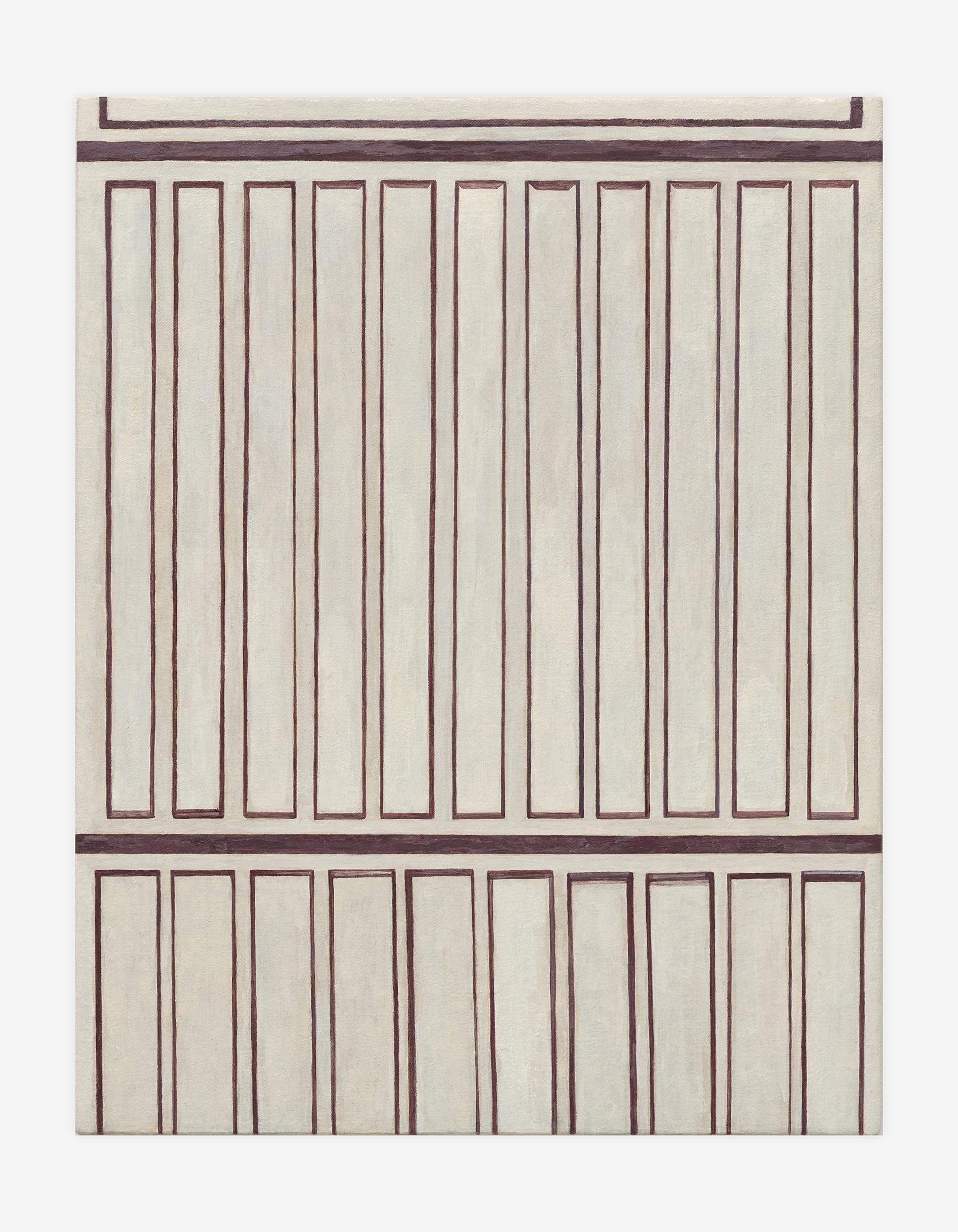

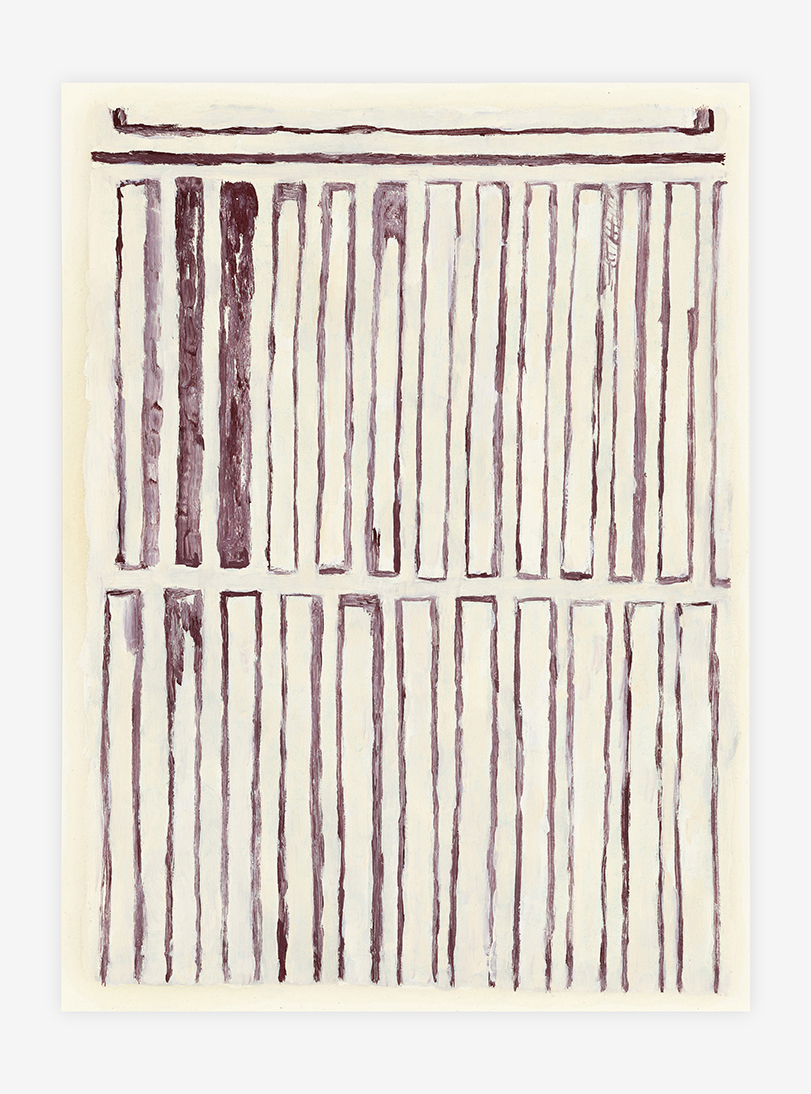

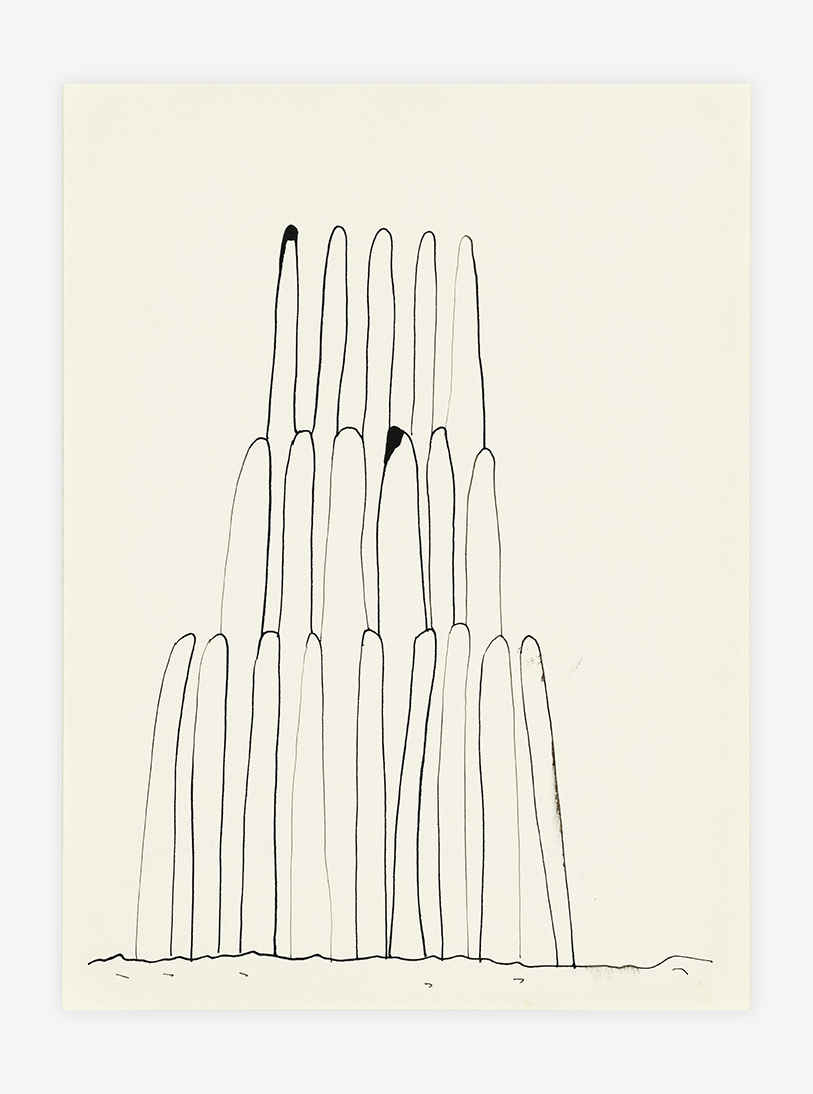

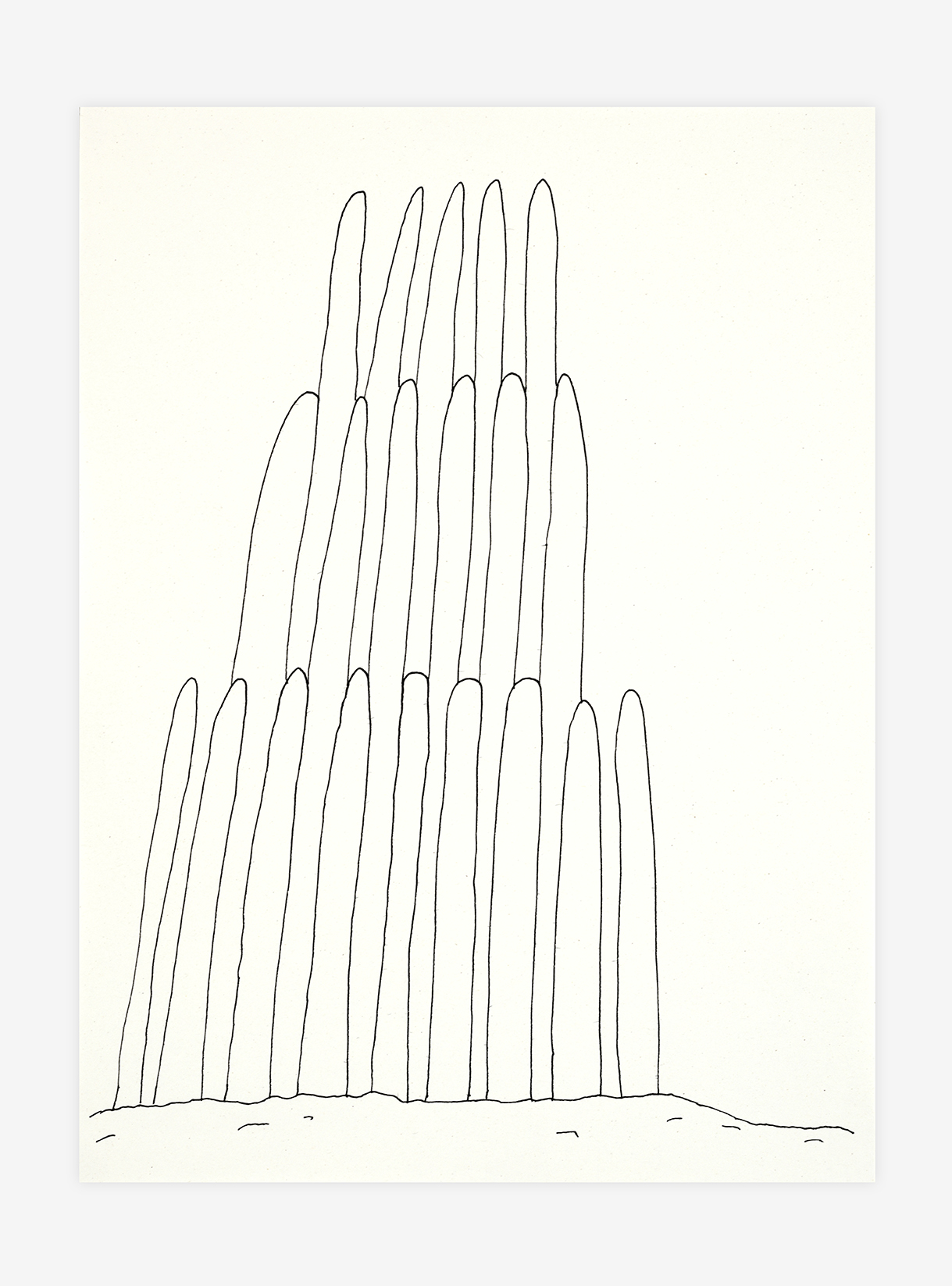

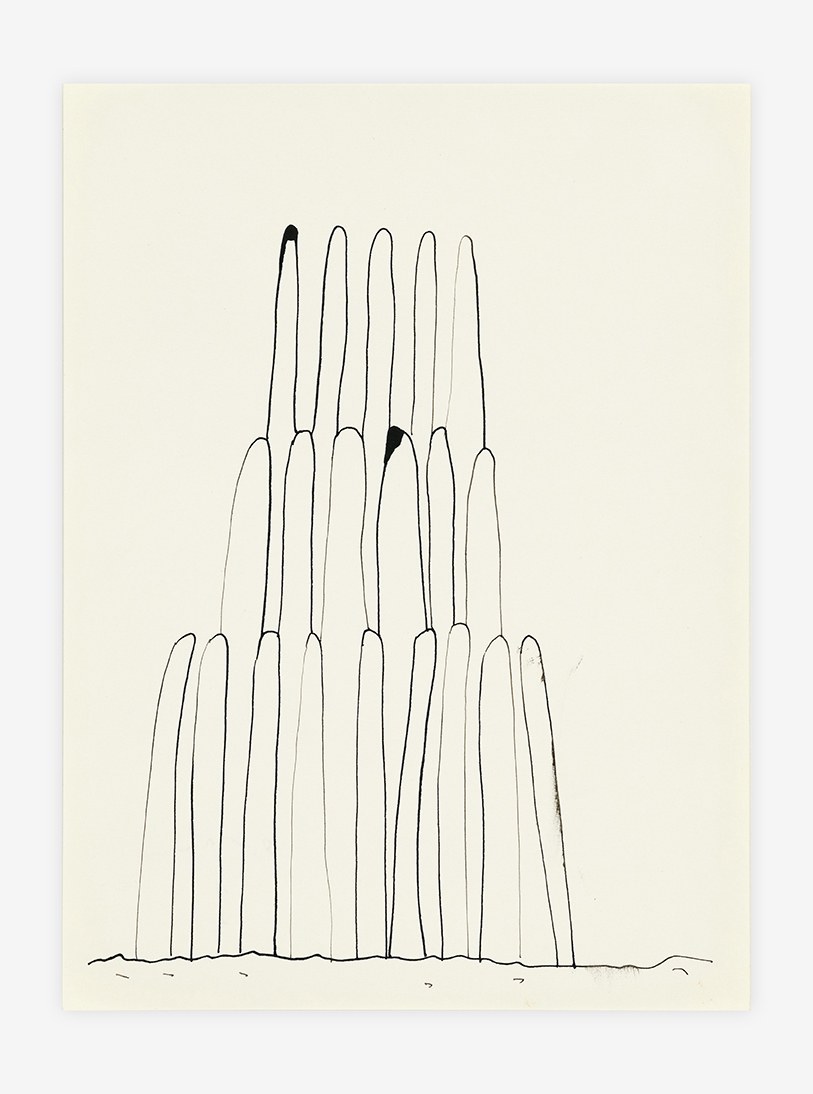

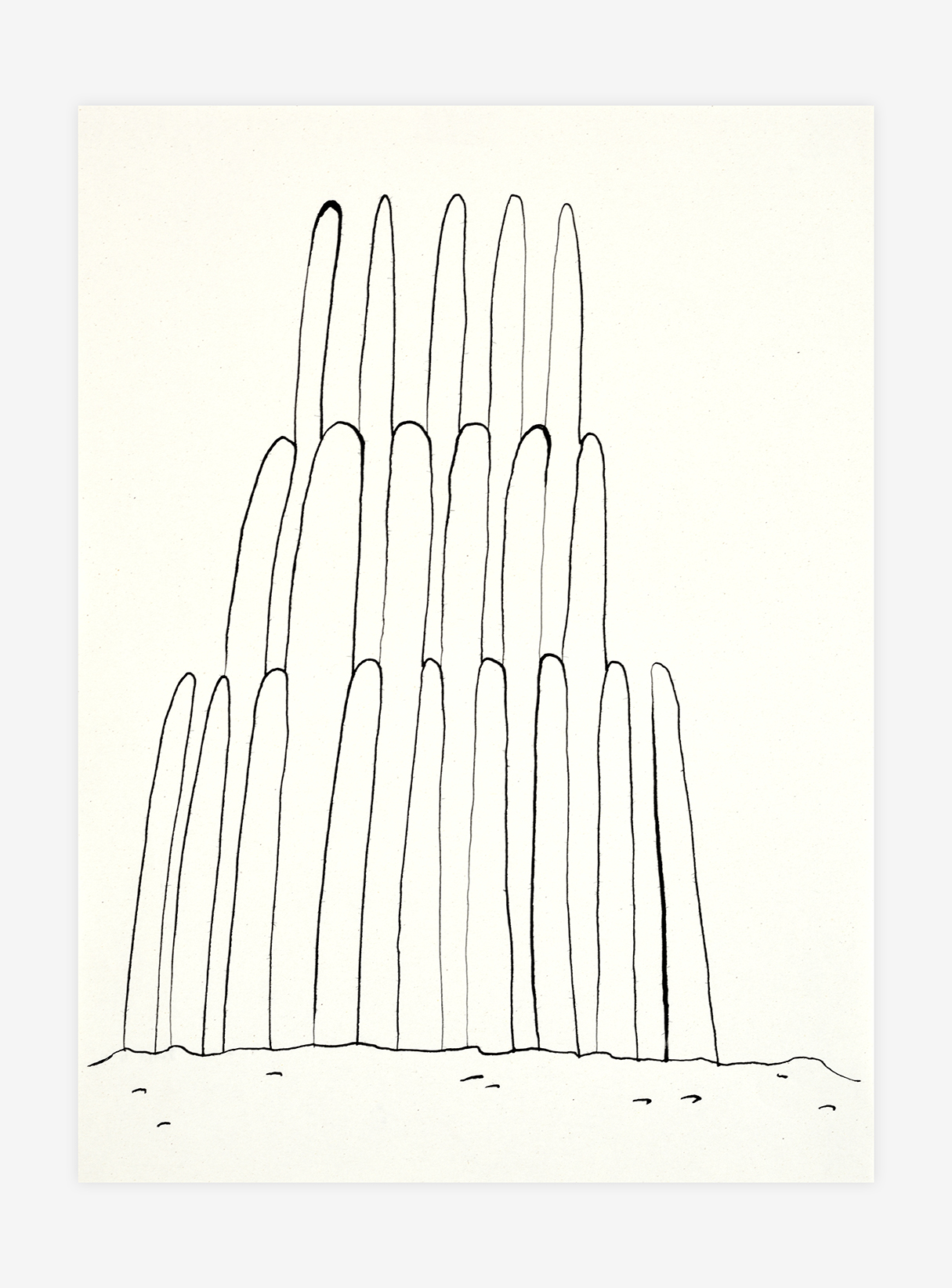

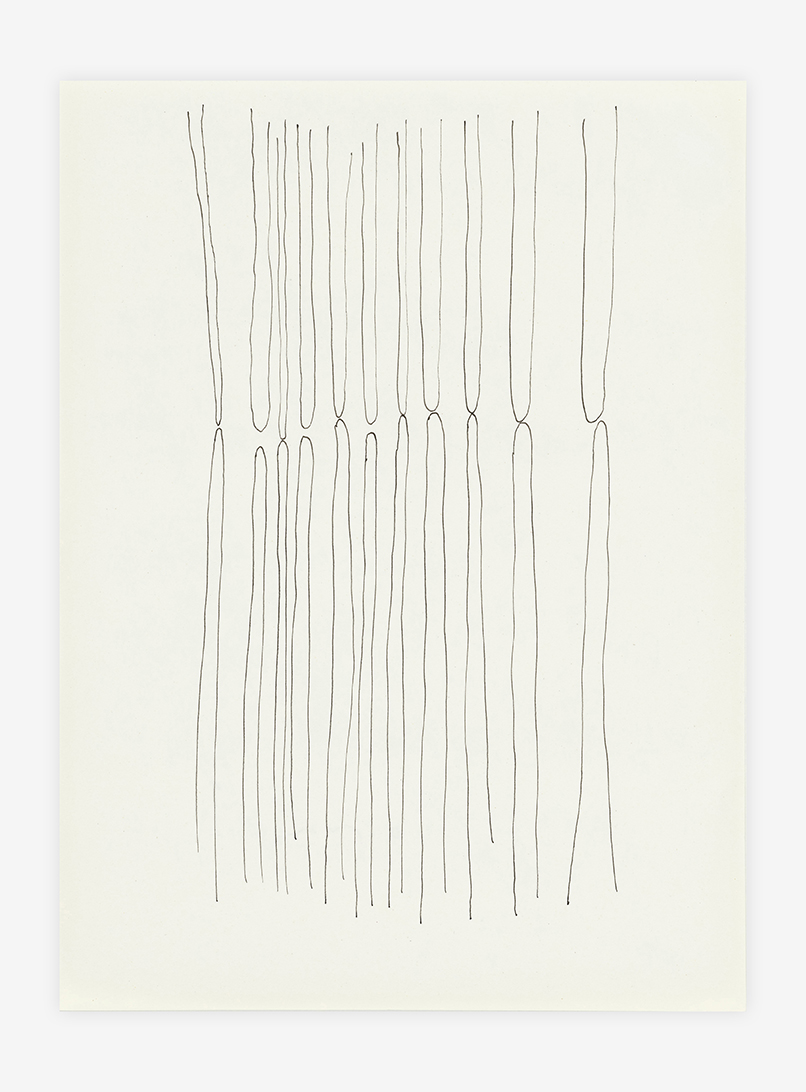

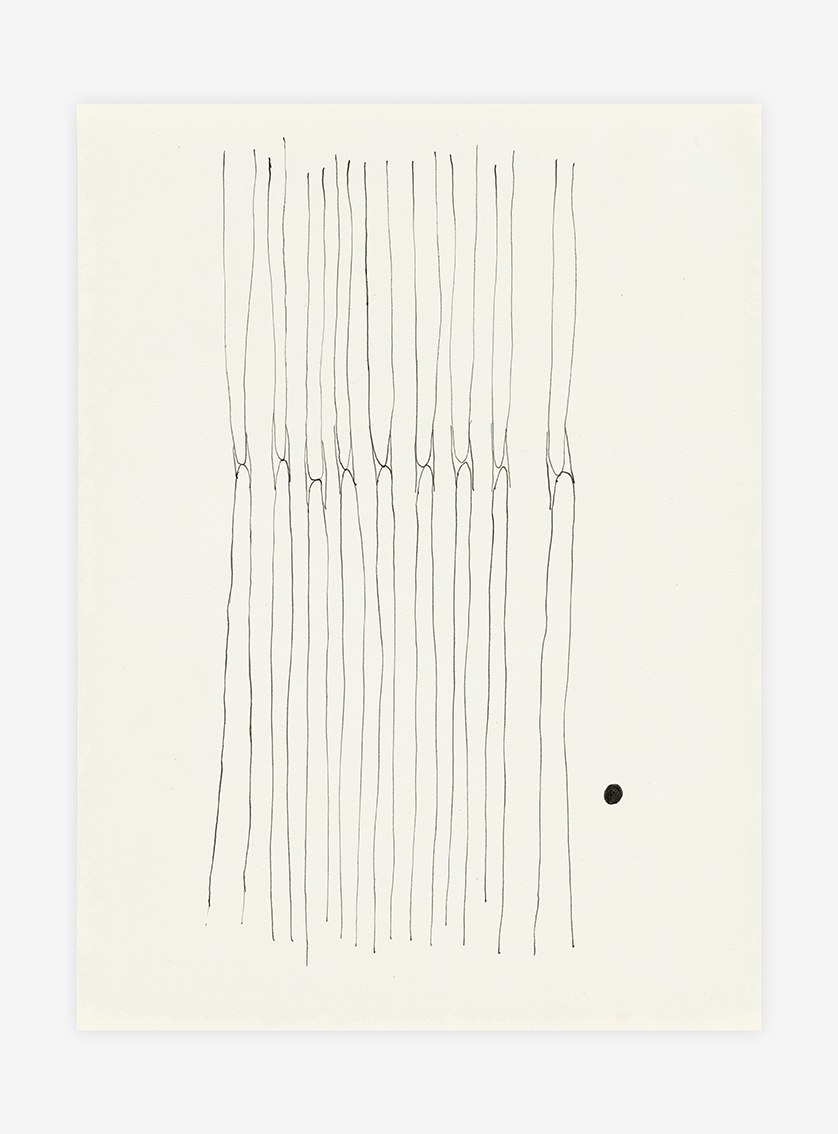

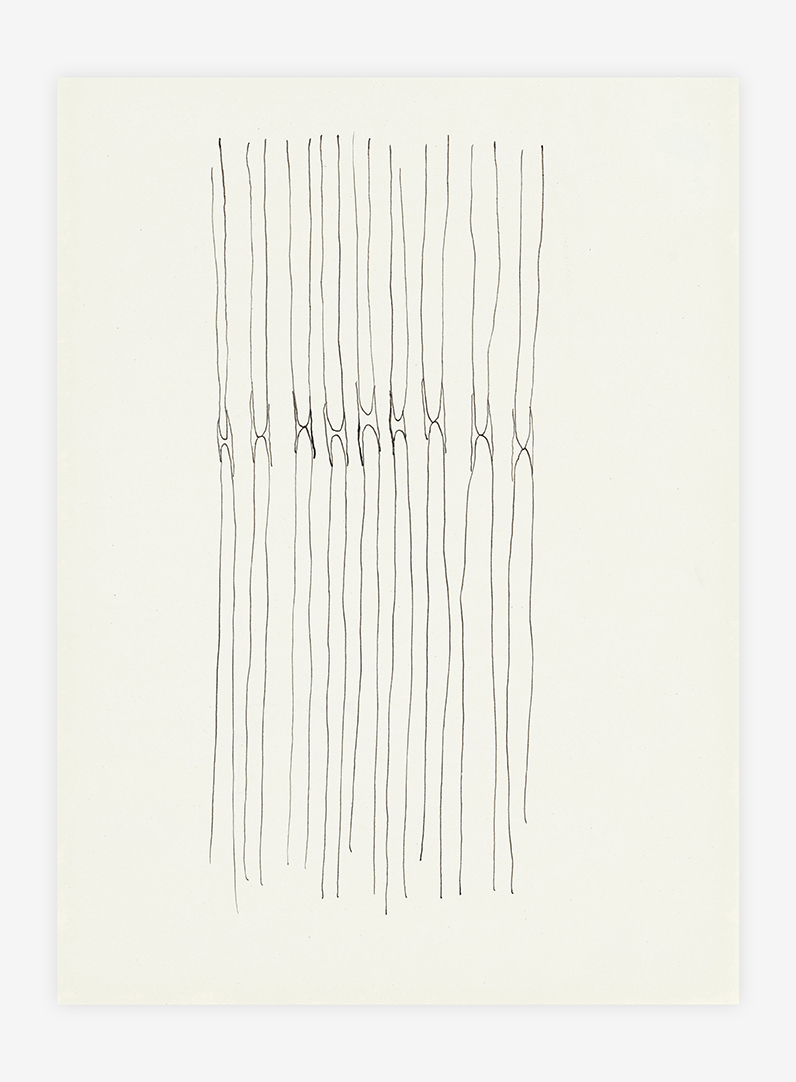

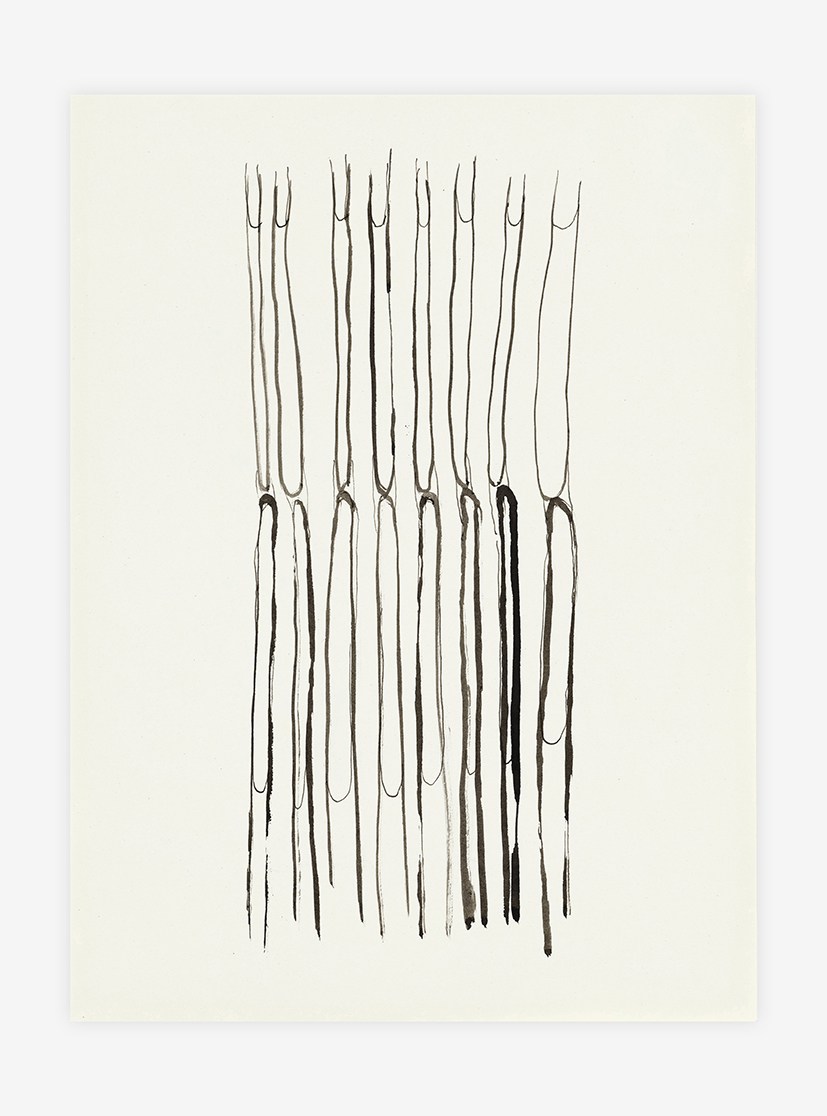

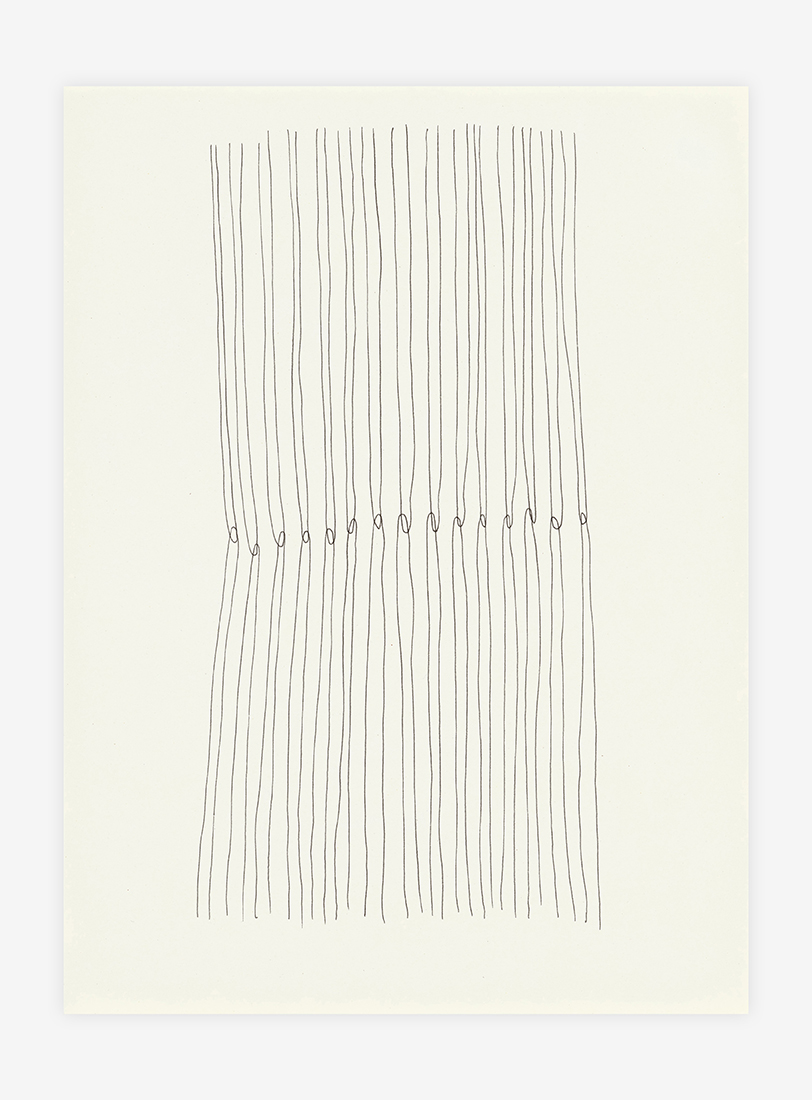

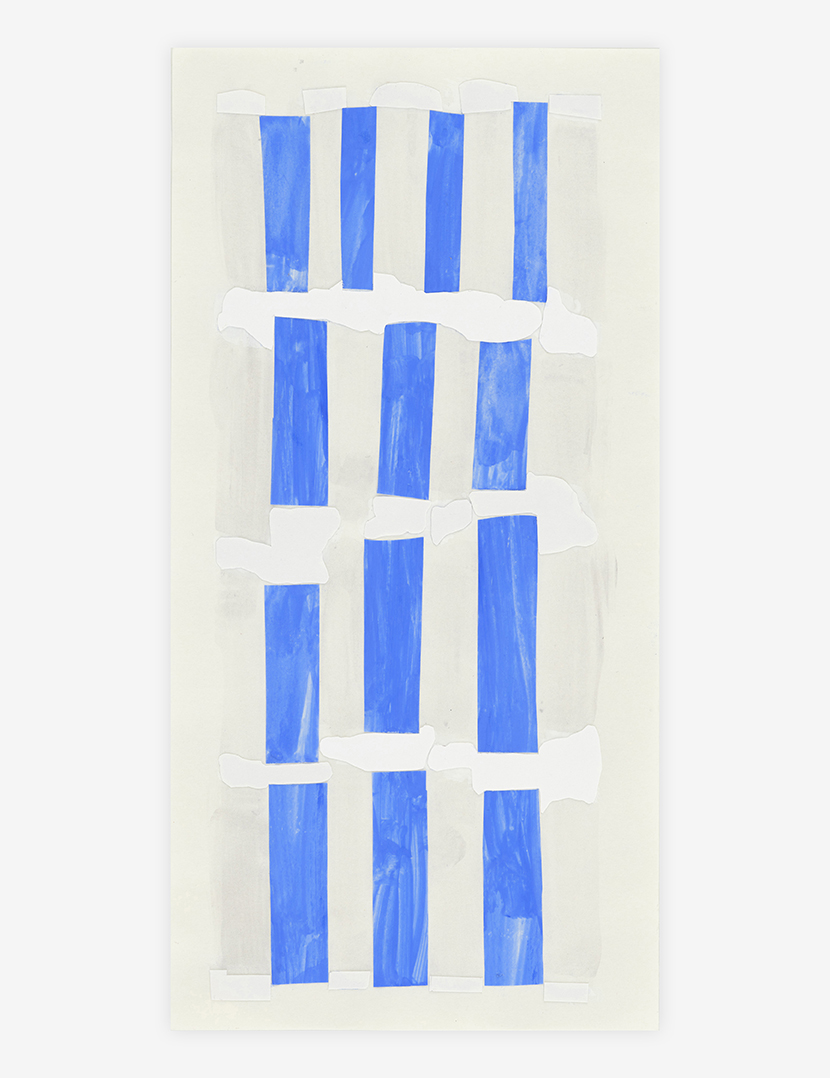

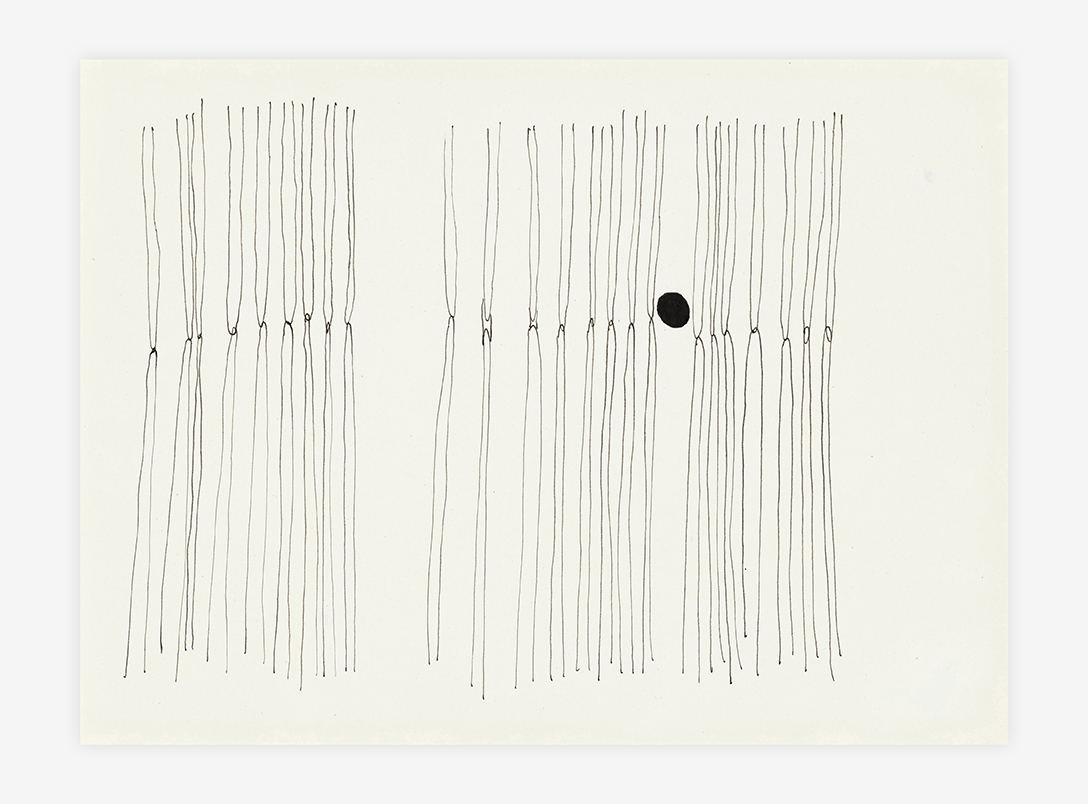

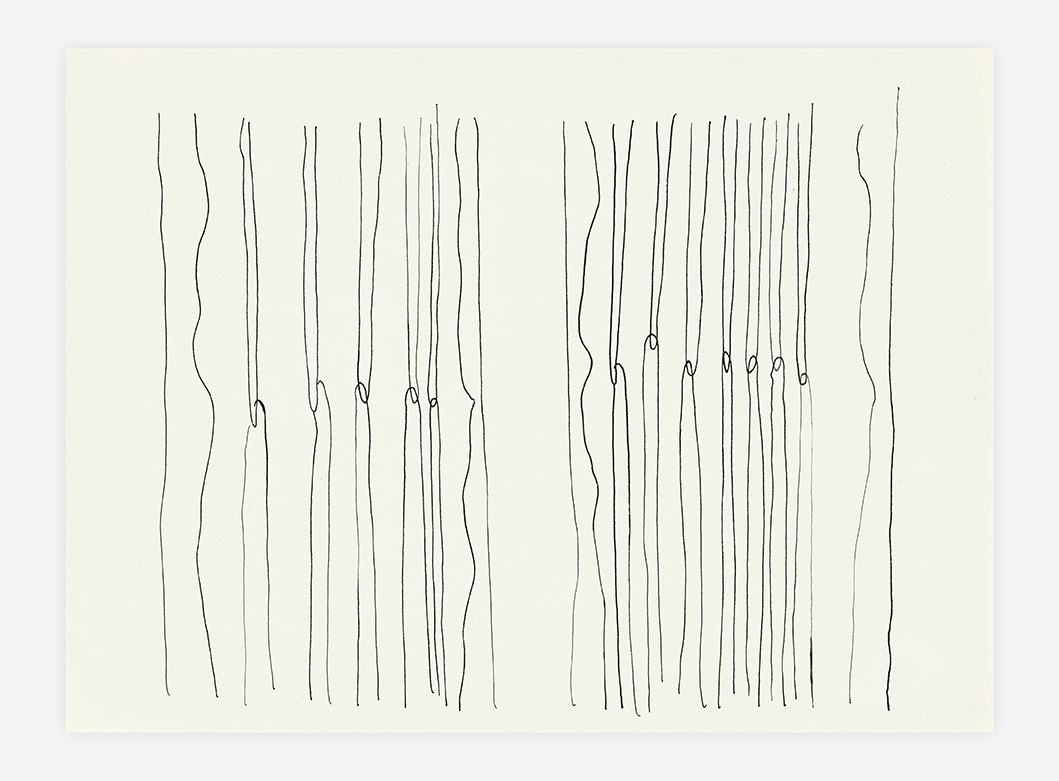

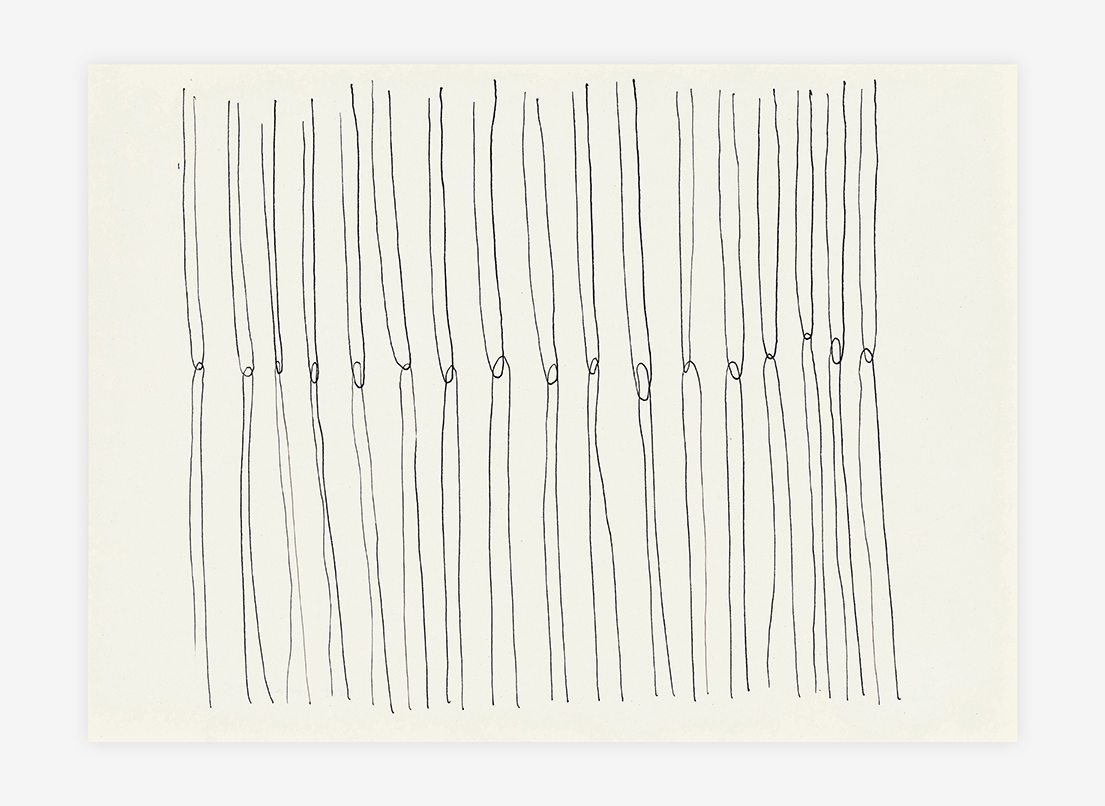

Neither crystalline brilliance nor splendor lie hidden in rusty corrugated iron; instead, it embodies pragmatism, protection, color, and time, along with its own surface texture. Despite their makeshift appearance, the metal sheets possess a fundamental strength: they protect the interior of a building from cold, heat, water, and snow. During a longer stay in Japan, the artist’s attention was repeatedly drawn to one of these facades: Mashio’s “Wellblech Bilder” are based on her first encounter with that specific facade, on its initial impact, or rather impression, on an aspect that would change with each new visit. This place provided a kind of “hold” to the artist, and occasion to find an answer what to paint – how to go on with painting.

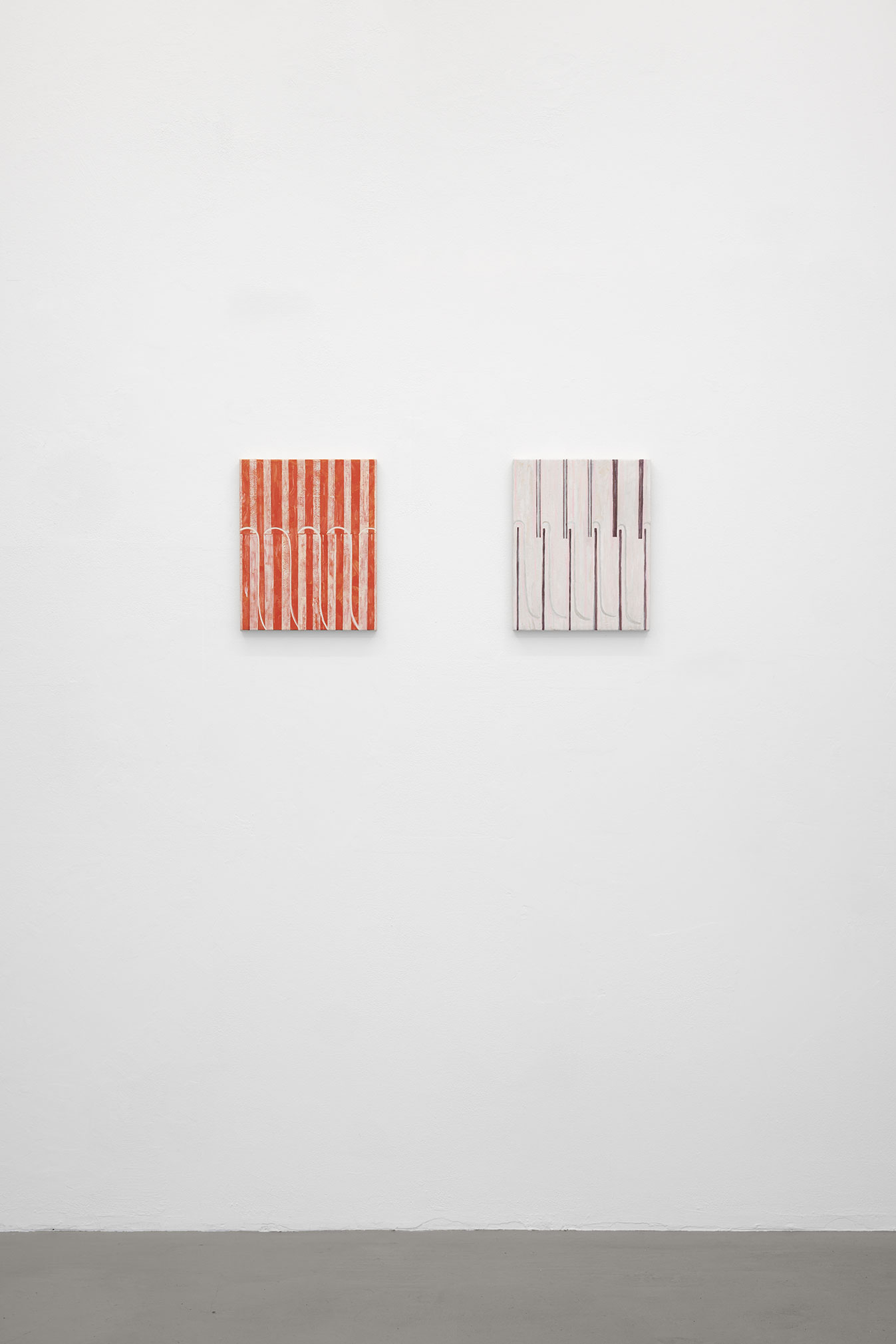

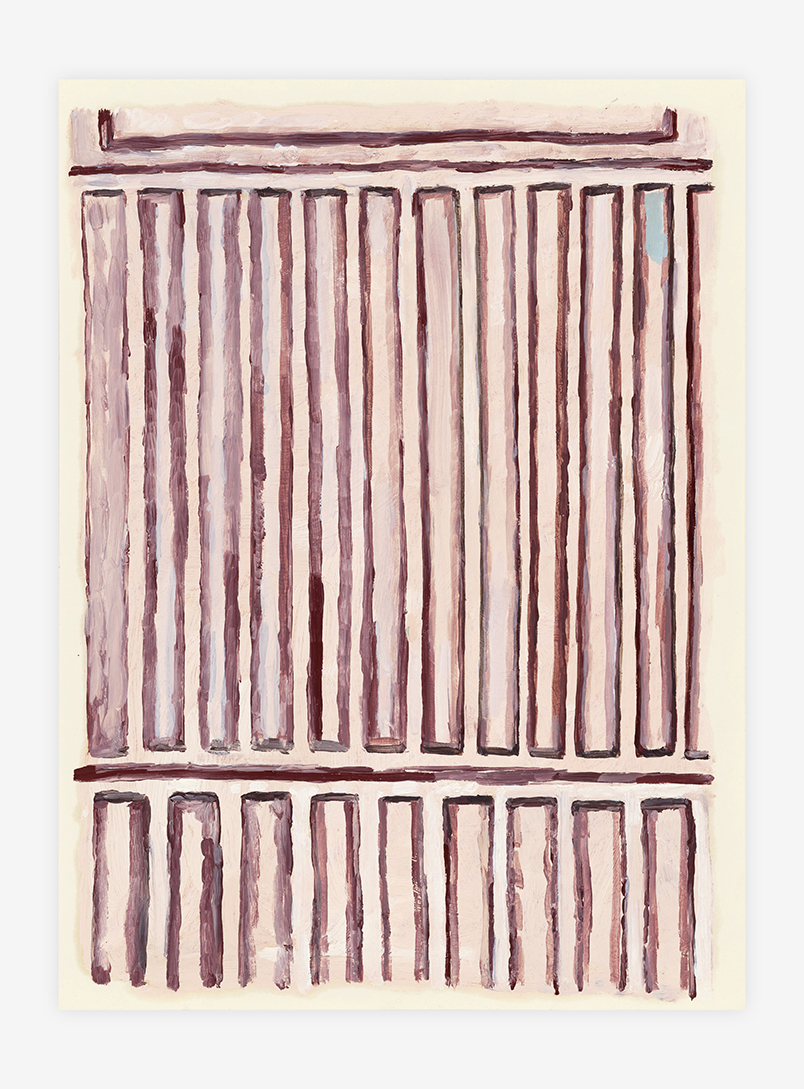

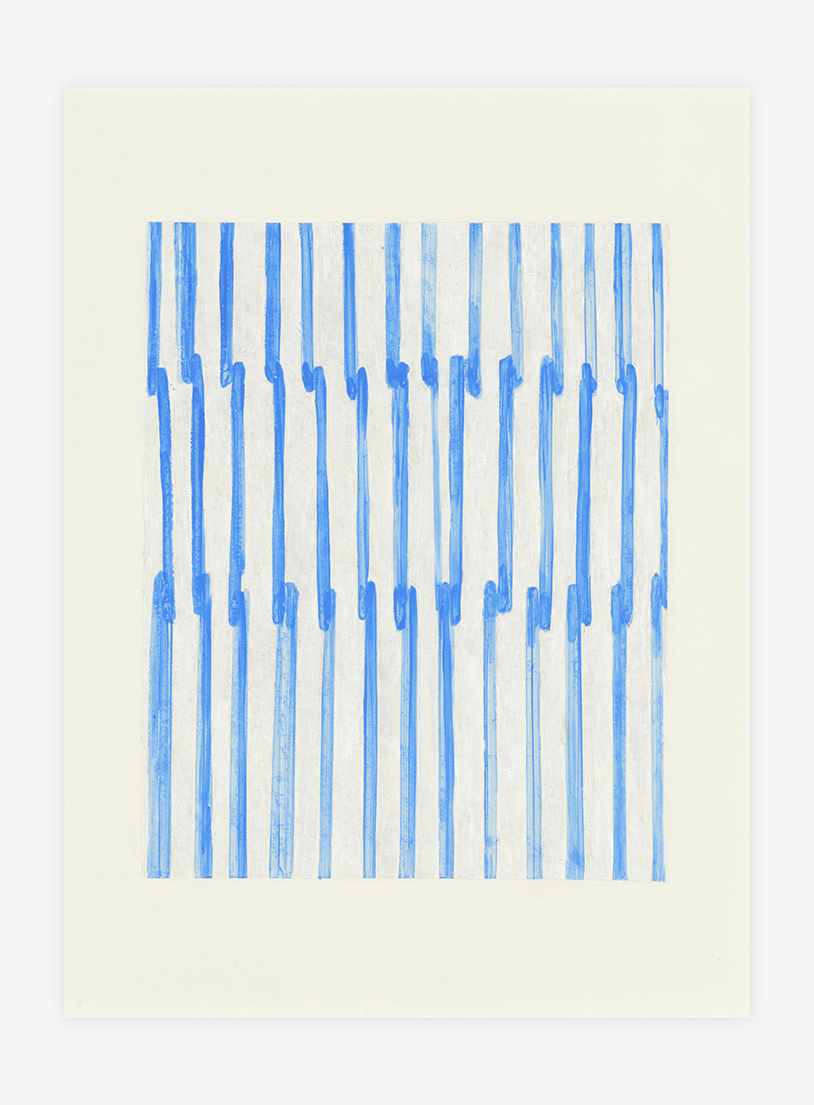

While the initial pictures are still directly inspired by the rusty, brownish color of the facade, they gradually shift their focus to skin, and perhaps therefore to the body as the place where memory is contained. According to the Cultural Scientists Jan and Aleida Assmann, recalling memories is much less to do with the actual moment being remembered than it is to do with the present from which the past is being reformulated. Mashio’s work on this series also regresses backwards into the future, inching toward a moment in the past that is constantly rejuvenating itself. The rusty corrugated iron is also a kind of skin, one that has been beaten by rain, typhoons, and storms.

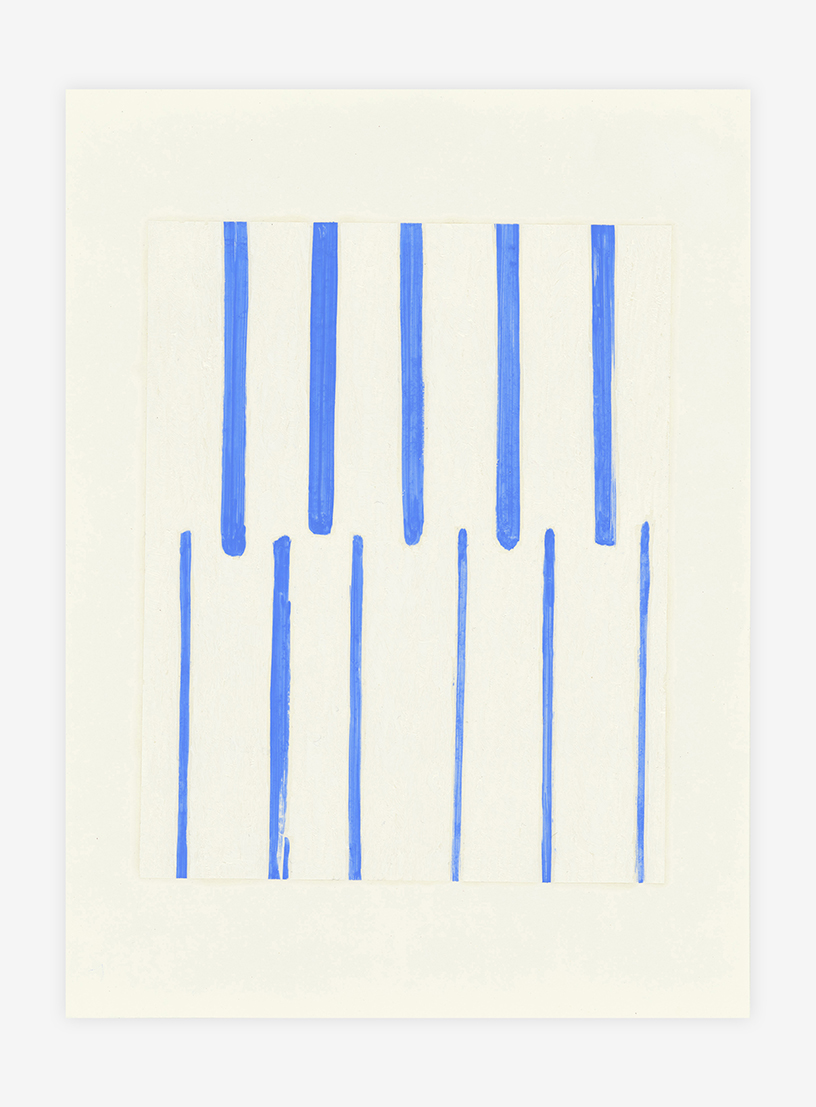

Over the following years, the skin colors blur with those of the rust and the sky, while the corrugated iron structure remains a constant, no matter how far the painting differ from the initial representation of the façade. Occasionally this results in a kind of eroticism about the imperfection of these paintings, which demonstrate the rare ability to mock their own resistance toward conventional notions of beauty; this can be seen in their porous surfaces, undulating image supports, anarchic paint mixtures of pigment and glue, as well as the outlines of the increasingly dissipated echoes of the corrugated iron structure. Each picture speaks: soft whispers, groaning murmurs, grating nuances, while a strange candor about the desire to create art emerges—perhaps because each painting is only one part of a larger family.

I love listening to Kaoli Mashio speak about her work. She talks about how the lines meet, how each picture is the vessel of an experience she preserves in it. Ultimately, these images represent counterparts for the artist, perhaps somewhat akin to portraits, which diverge further and further away from the corrugated iron matrix in which they are embedded and take on a highly nuanced independent existence. In 2011, Chris Kraus published a volume of essays titled “Where Art Belongs.” In short, it reclaims lived time as a material in the creation of visual art. Kraus chronicles the small forms of resistance to digital disembodiment and the hegemony of the entertainment, media, and culture industries, as well as the sometimes doomed but persistently heroic efforts of artists and groups to reclaim space and time.

Despite all its faults, Kraus argues, the art world remains the final frontier for the desire to live differently. Mashio’s experience-driven paintings invert Rosalind Krauss’s canonical position on grids as emblems for the autonomy of modernism: While the grid is still a signifier for the autonomy and self-referentiality of art, the artist transforms it to claim a personal form of independence. Her images exist freely and autonomously as a snapshot of a particular moment.

Martin Germann